On Nov. 2 a century ago, engineer Frank Conrad, a little bit the maverick, went where no man had gone before — into a little shed atop the tallest building in Westinghouse’s East Pittsburgh plant to broadcast history’s first radio news event, Warren G. Harding’s presidential victory over fellow Ohioan James M. Cox.

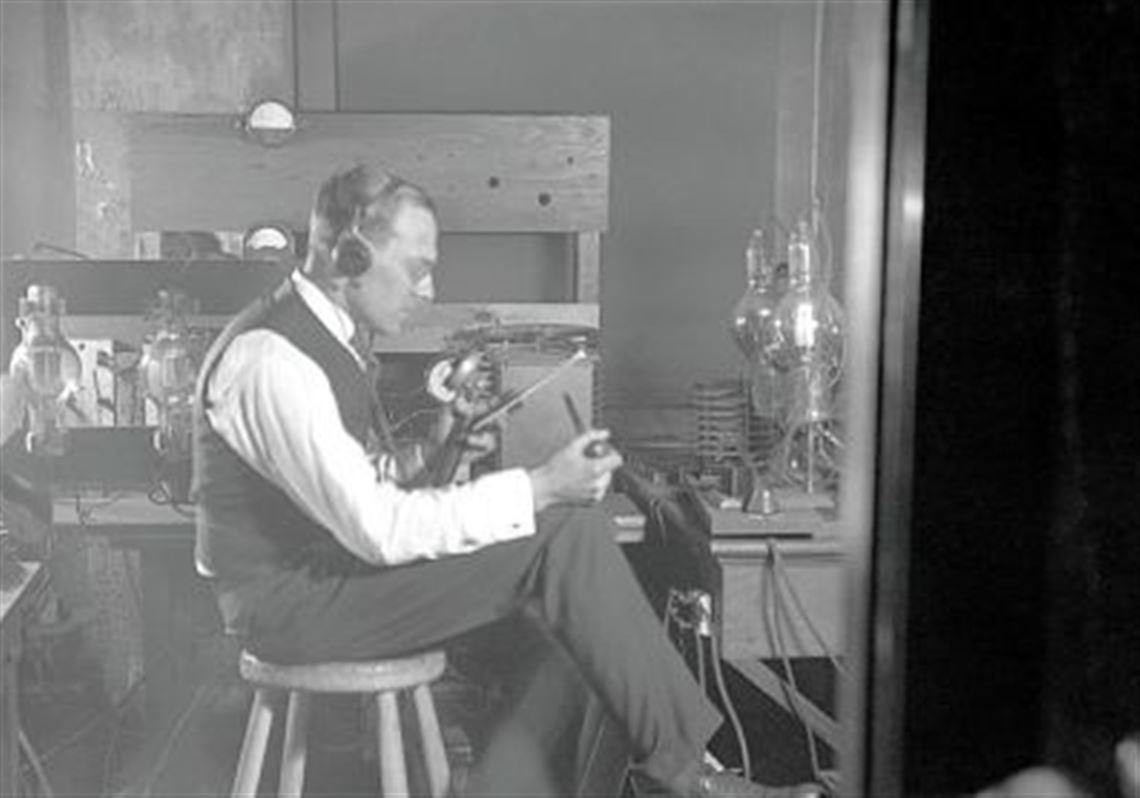

The shed was equipped with an antenna, a 100-watt transmitter, a candlestick telephone “microphone” buffered in a cardboard box and several chairs.

Conrad had tinkered and innovated for years to bring KDKA radio into being. Its commercial license had been issued just six days before the election, and only a few thousand people had receivers to hear the results.

But the event went viral for its day.

Two years later, the U.S. Department of Commerce had licensed 500 radio stations broadcasting to mass audiences.

KDKA’s 100th anniversary is being commemorated Monday and Tuesday in a replica of that little shed. Duquesne University and the National Museum of Broadcasting have collaborated on several events that will be live streamed on YouTube, with a link here.

Duquesne University President Ken Gormley will narrate an almost hour-long documentary about KDKA’s pioneering legacy at 7 p.m. Monday. 2. A live celebration will follow.

On election night, Tuesday, starting at 8 p.m., KDKA personalities and Duquesne University officials will discuss parallels between the 1920 and 2020 elections and the importance of KDKA and its role in the original broadcast.

That broadcast will be re-enacted with help from radio historians.

In 1920, the Pittsburgh Post, predecessor of the Post-Gazette, supplied periodic election returns to the broadcasters in the shed, then they announced the results to listening parties around Pittsburgh and across the Midwest, Mr. Gormley said.

Mr. Gormley served as mayor of Forest Hills in the late 1990s when the Westinghouse company gave the borough its lodge building during a divestiture, he said. And having grown up with the Westinghouse legacy all around him, he said he was interested in keeping the history alive.

Rick Harris of the National Museum of Broadcasting approached Mr. Gormley four years ago to discuss plans for the 100th anniversary. The coronavirus forced an abbreviated, virtual celebration that is expected to include Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto and Frank Conrad’s grandson, actor David Conrad.

“I couldn’t bear the thought that this anniversary would pass and we wouldn’t have done something about it,” Mr. Gormley said. “It’s a real Pittsburgh moment that needs to be celebrated.”

Frank Conrad was the force behind that Pittsburgh moment.

Westinghouse had been a defense contractor during World War I, when Conrad was an engineer working on radio technology. He experimented in his garage, using bare wires, crackling spark coils, homemade vacuum tubes and a candlestick telephone for a microphone.

As part of his research and for fun, he began broadcasting music shows into the airwaves — mostly recorded music and sports scores. He hired his sons as announcers and pianists, and their Saturday night piano shows earned newspaper coverage early in 1920.

KDKA100.org states that Conrad’s innovations “motivated Westinghouse to commit to further shortwave research. Frank Conrad had become the force behind the birth of American shortwave broadcasting.”

The first KDKA broadcast voice was that of Leo Rosenberg, who announced to listeners on the night of Nov. 2, 1920, “This is KDKA of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. We shall now broadcast the election returns.

“We are receiving these returns through the cooperation and by special arrangement with the Pittsburgh Post and Sun. We'd appreciate it if anyone hearing this broadcast would communicate with us as we are very anxious to know how far the broadcast is reaching and how it is being received.”

Mr. Harris, a co-founder of the National Museum of Broadcasting, which exists without a physical home, said Pittsburgh’s legacy cannot be overstated, considering that radio was the forebear of television, cellular and online technology.

“Radio was the first technology in people’s lives, and although a lot of people may not realize it, our smartphones have radios in them,” he said. “AM-FM, shortwave, TV, cellular, the internet — all of that descended from the technology that was developed in Pittsburgh more than 100 years go.”

Before 1920, there were no commercial broadcasts.

Conrad was such an innovator that he expanded his horizons beyond what the government intended.

“The government gave KDKA that commercial license so they could broadcast among their plants,” said Don Maue, Duquesne University’s director of the Center for Emerging and Innovative Media. “But Frank [Conrad] asked, ‘Why don’t we broadcast so that people don’t need a license to listen?’ Frank was something of a maverick.”

Mr. Maue is an amateur ham radio expert and radio history scholar who helped prepare the anniversary celebration content.

“As a faculty member, one of my roles is to make the past relevant and have it inform the future,” he said, adding that there is no intertwining of past and future quite like wireless. The radio used to be called the wireless, and now there is wireless internet, he said. “An iPhone has four radios built into it, the same technology but far advanced.”

As the 1920s progressed, Westinghouse led America into the brave new world of radio technology — making receivers and selling them. What had started as a side business turned into a $270 million business, Mr. Maue said.

“And by the 1930s, the radio was part of the family.”

Diana Nelson Jones: djones@post-gazette.com

First Published: October 28, 2020, 7:28 p.m.