Pittsburgh’s identity as the Steel City was jolted last week by word of the proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel by Tokyo-based Nippon Steel for $14.1 billion.

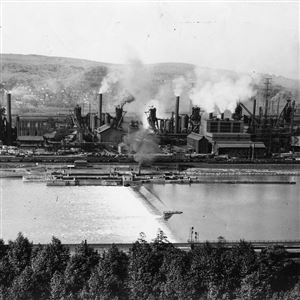

At issue is Pittsburgh’s love-hate affair with steelmaking, which created unheard of prosperity and jobs for the city before turning into a prompt for polluted air, shuttered storefronts and the Rust Belt.

Andrew E. Masich, president and CEO of the Senator John Heinz History Center in the Strip District, calls it our “good and bad connection with steel.”

“It’s part of our heritage, our history, our DNA,” he said. “I just hope we can remember what steel has meant to our community.

“I have a feeling it will stay part of our character.”

Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill, which became part of U.S. Steel in 1901, opened in Braddock in 1895, but the region’s link to metal making stretches back much further, with the city’s first iron foundry opening in the late 1700s, thanks to Pittsburgh’s rich coal deposits.

All that’s long gone, of course, with the economic shift to medicine and higher education transforming the city for 40 years with the rise of hospital giant UPMC, Pennsylvania’s biggest non-government employer.

Consider the changes in the city since big steel’s arrival more than a century ago: UPMC, headquartered in Downtown’s 64-story U.S. Steel Tower, reported $26 billion in operating revenue last year; for the same period, U.S. Steel booked $21 billion in revenue.

Still, the image persists. Since 1990, more than 120 motion pictures have been shot in Pittsburgh, some mining its gritty vibe, even though the region has been moving away from smokestack industries for decades. The region’s last steel producer soon may no longer be locally owned, but Pittsburgh Film Office Director Dawn M. Keezer said “Pittsburgh and steel will go together forever.”

“There’s still people with the image that we’re producing steel in the city, which we haven’t done for years,” she said. “For film producers, it’s not about what it is, but what it looks like.”

A backdrop for filmmakers out to capture images of industrial decline, according to Ms. Keezer, has been the Carrie Blast Furnaces in Swissvale and Rankin, built in 1884 and now a National Historic Landmark. The furnaces, which produced molten iron, went cold for the last time in 1982.

In addition, one of the iconic images of the region, the huge likeness of folk hero Joe Magarac, a steelworker who bends red-hot steel beams with his bare hands, was moved from Kennywood to U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson plant gate in 2009, connecting the legendary with the real.

Joe Magarac was fictional, but the Western Pennsylvania work ethic that built Pittsburgh’s steel industry certainly wasn’t.

Joe Zeff, who returned to his hometown after 29 years away in 2021 with the decision to move his marketing firm, Joe Zeff Design Inc., to the South Side from New York City, noted that his father operated a crane in a Braddock junkyard.

Mr. Zeff, 58, was the first in his family to graduate from college, a pattern embroidered into the region’s social fabric. But the Greenfield native prefers to look ahead rather than back after word of U.S. Steel’s acquisition for $14.1 billion

“Part of my personal mission, as much part of a professional mission, is to help people rediscover Pittsburgh, that we’ve evolved beyond steel,” said Mr. Zeff, who counts upstart Pittsburgh Robotics Network among his clients. “My father worked in the steel industry, so it’s in my blood. But at the same time, I recognize that time moves on.”

Instead of Pittsburgh’s steelmaking legacy, he would rather talk about Mill 19 in Hazelwood, a former steel mill that is being turned into a research center for robotics, advanced manufacturing and self-driving vehicles, and the North Shore’s Astrobotic’s Peregrine Lander, which is headed for a moon landing.

Lots of Pittsburghers may embrace appearance as reality, with acceptance a way of coming to terms with the idea that local ownership of the Pittsburgh area’s last steelmaking operations is slipping away. But labor relations historian Charlie McCollester went a step further: He welcomed news of the sale, saying U.S. Steel’s labor relations have been poisoned for generations.

Japanese ownership may bring a change for the better for workers, he said.

“I’m fairly optimistic about Nippon Steel although I know nothing about it,” said Mr. McCollester, retired director of the Pennsylvania Center for the Study of Labor Relations at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

“I respect Japanese manufacturing. U.S. Steel has been cursed with very poor labor relations since the Homestead strike of 1892,” when armed guards hired by Carnegie Steel battled strikers, leaving 16 people dead and ultimately breaking the union.

“We crushed our working class,” said Mr. McCollester, a one-time union machinist. “Steel has been in deep trouble here for a long time.”

The sale means Pittsburgh will have one fewer Fortune 500 company calling the city home, a list that still includes PNC Financial Services Group, PPG Industries and Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies. And although Monday’s joint announcement said U.S. Steel would retain its name, brand and headquarters in Pittsburgh after the sale, all bets are off when the ink dries.

Think: storied Pittsburgh company H.J. Heinz before it merged with Kraft Foods Group in 2015 and moved half of its executive operations to Chicago.

Regardless of the good that may come from the sale of U.S. Steel, it’ll still be a bitter pill for union members who remember the early 1980s, when bashing Toyotas with a sledgehammer became a popular fundraiser — at $1 a whack — to protest Japanese steel import prices that were lower than the cost of production.

The United Steelworkers of America, which represents employees at three U.S. Steel plants in the faded Monongahela Valley, are opposing the sale along with an array of elected officials who are leveraging public angst over the deal.

The deal, which is expected to close in October, still has to be approved by U.S. Steel shareholders and federal regulators.

Pittsburghers may have forgotten Joe Magarac, the mythical steelworker created in the 1930s, but they’re more likely to recognize Steely McBeam, the Pittsburgh Steelers mascot created before the 2007 season. And regardless of who owns the company, Pittsburgh football player helmets will continue displaying the four-pointed starlike emblem in a circle, which was trademarked by the steel industry in 1960.

“In some ways, it’s bittersweet that U.S. Steel was sold to a Japanese company,” Mr. Zeff said. “But just as Heinz left Pittsburgh, that ketchup bottle continues to be part of our identity here. It’s healthier to embrace the change than to fixate on the rearview mirror of what once was.”

Kris B. Mamula: kmamula@post-gazette.com

First Published: December 24, 2023, 10:30 a.m.

Updated: December 25, 2023, 2:47 a.m.