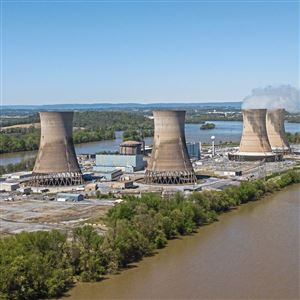

HARRISBURG — Gov. Tom Wolf plans to join a coalition of regional states to set a mandatory, shrinking cap on the amount of carbon dioxide that can be released from Pennsylvania’s fossil fuel power plants.

Mr. Wolf issued an executive order on Thursday directing the state Department of Environmental Protection to draft regulations to join the nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a carbon cap-and-trade program with a shared market that has netted its member states $3.2 billion since the program took effect in 2009.

Owners of carbon-emitting power plants would pay hundreds of millions of dollars a year at current prices, which Pennsylvania could direct toward energy efficiency, renewable energy and other projects designed to reduce the release of climate-warming gases.

The move would hasten Pennsylvania’s shift away from dirtier fuels like coal and vastly expand the scope of the nation’s first mandatory market-based carbon-cutting initiative.

Pennsylvania has the fifth-highest power sector carbon emissions in the country, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Power plants in the Keystone State emit more greenhouse gases than those in all of the initiative's current member states combined.

“We are in a climate crisis,” Mr. Wolf said at a morning press conference where he delineated hundreds of millions of dollars in property damage caused by record rains in Pennsylvania in 2018. “Someone has to pay to fix the destroyed houses, roads and bridges and that’s going to be all of us.”

“While setting goals and targets is absolutely important we cannot delay any longer in taking action.”

Mr. Wolf, a Democrat, had sought authorization from the Republican-controlled Legislature to start the process of joining the initiative during budget negotiations this spring, but did not reach an agreement in time for the final spending deal.

Now, administration officials say Mr. Wolf has the authority under the state’s existing air pollution law to join the program without the Legislature’s approval, although they say the go-it-alone approach would limit the uses of the funds to state programs designed to curb air pollution.

Some Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative states have used proceeds from their carbon auctions for broader initiatives, like directly reducing consumer energy bills or making transfers to state general funds.

Mr. Wolf said he intends to work with the General Assembly and other stakeholders to help design the program and decide how to spend its revenues.

“We know that this cannot be done in a vacuum,” he said.

Legislative pushback

Several state lawmakers are trying to block the Wolf administration’s approach. Bills being drafted in the House and Senate would prohibit the governor from joining Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or otherwise establishing a carbon price without the Legislature’s approval.

House Republican leaders vowed on Thursday to use “the fullest extent of our legislative power” to demonstrate that the governor does not have the power to enlist Pennsylvania in a binding, multi-state agreement without the General Assembly’s support.

“Our state is not an autocracy,” they said in a statement, “and one-sided decisions as significant as this leave out the important voices of Pennsylvania workers, communities and families whose livelihood is built upon important sectors of our energy economy.”

Senate Republican leaders named four factors that must be included in any carbon-cutting plan, including maintaining the diversity of Pennsylvania’s energy portfolio — which is currently dominated by gas, coal and nuclear — and requiring that RGGI’s other member states “utilize all aspects” of that portfolio.

They also called for keeping energy prices affordable and implementing the plan in “an appropriate legal manner.”

The debate over a carbon price is not neatly partisan in Pennsylvania.

Some Republicans who want to preserve the state’s existing fleet of nuclear plants support the idea because it would benefit electricity sources, like nuclear and solar, that don’t have smokestack emissions of greenhouse gases. Some Democrats from areas that mine or burn coal oppose it out of concern that it may force power plants and mines to shut down.

Mr. Wolf may face a legal challenge either way.

A group of environmental, citizens and faith groups petitioned the state’s environmental rulemaking board last year to adopt an economy-wide carbon cap-and-trade program that would be much more sweeping than participation in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. One of the lead attorneys on the petition said Tuesday that he will sue the commonwealth if regulators reject the petition without offering a viable alternative.

How it works

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative currently includes Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. New Jersey is rejoining the coalition in January after leaving in 2012 and Virginia may begin participating in 2021.

Each member state designs its own carbon budget and trading program — either through law or regulation — based on the coalition’s model rule, but they agree to share broad goals and market infrastructure, Franz Litz, a consultant on cap-and-trade programs, told the state’s climate change advisory committee on Tuesday.

Coal, gas and oil-fired power plants with a capacity of 25 megawatts or more must buy a credit for every ton of carbon they emit. The price for each carbon credit — or “allowance” — sold at the most recent auction in September was $5.20.

The regional emissions cap will shrink by about 3 percent a year from 2021 to 2030.

Mr. Wolf’s executive order says Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative states have collectively reduced their power sector carbon emissions by over 45 percent since 2005.

Pennsylvania’s power sector had a 28 percent reduction over the same time period, largely because lower-emitting natural gas plants are displacing coal plants in the competitive power market while improved energy efficiency has kept demand relatively flat.

‘Modest program’

Members of the climate advisory committee questioned how much of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative states’ reductions could be attributed to the cap-and-trade program.

Mr. Litz said an important feature of the program is that it ensures emissions keep declining.

“It's a fairly modest program that has managed to lock in reductions — whatever their cause,” he said. “It would seem to be a tool that could get a state, or a group of states, to where the electricity sector needs to be by mid-century.”

The United Nation’s climate science coalition reported last year that global greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut to net zero by 2050 in order to avoid devastating increases in global temperatures.

Mr. Wolf’s executive order is the beginning of a process that he estimated will take two years to complete. He directed DEP to present a draft rule to the state Environmental Quality Board by July 31, 2020.

He said the process of crafting the rule should include “a robust public outreach effort” to ensure that it “results in reduced emissions, economic gains and consumer savings.”

Environmental groups praised the governor for what they called they most significant step Pennsylvania has ever taken to cut carbon pollution.

Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto said that by moving to join the initiative, Mr. Wolf "is helping to further innovation, create green jobs and respond strongly to the challenge of climate change."

Business and energy interests indicated they want to see how the process unfolds.

Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry CEO Gene Barr said his association supports market-based approaches to achieving environmental goals, but it also encourages legislative input in the process of developing greenhouse gas rules and an analysis of its impact on ratepayers.

A significant part of the review process will involve modeling the environmental and economic impacts of different policy paths, like what sources will be included in Pennsylvania’s carbon budget.

Some states, for example, have exempted particular types of generators from their budgets. Power plants that burn waste coal piles in Pennsylvania are likely to seek such an exemption.

Regulators must also work with the existing Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative states, who will assess whether Pennsylvania’s proposal is stringent enough, among other factors, before agreeing to accept a new partner.

Laura Legere: llegere@post-gazette.com.

Updated at 12:33 p.m. on Oct. 3, 2019

First Published: October 3, 2019, 1:00 p.m.