Even as the federal government that once promised tighter control over methane emissions now heads in the exact opposite direction, environmental groups and companies looking to capitalize on stricter controls have not been deterred.

Methane monitoring creates jobs, announced a report commissioned by the Environmental Defense Fund, a New York-based nonprofit that has been studying methane emissions from the oil and gas sector for years.

To illustrate the point, EDF invited a helicopter company that flies over well sites and pipelines to give rides in search of methane leaks on Tuesday. Spoiler alert: None was found.

An analysis by North Carolina-based firm Datu Research LLC turned up at least 60 companies providing methane leak detection and repair services to the industry in the U.S. And when Datu’s president, Marcy Lowe, called these firms to survey them about their work, she found many too busy to talk.

No one is ever at their desk, she said. They’re up in planes and helicopters outfitted with methane leak detectors, in cars driving around with gas sniffers, walking pipelines, piloting drones and installing lasers to pick up leaks at oil and gas wells.

The majority are small businesses, Ms. Lowe reported, and a third are startups.

All expect to grow.

Still, Ms. Lowe said, “A lot of the companies told us that policies matter. They really are tying these businesses to new rules.”

That’s tricky these days. Whereas a year ago the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was collecting data on methane emissions from the oil-and-gas sector as a prelude to writing regulations to limit them, the current leadership of the agency has told oil and gas companies not to bother sending in their emission inventories.

Federal rules appear unlikely.

Some states are picking up the slack. Colorado, Wyoming and Ohio have passed rules requiring leak detection and repair programs in recent years, and Pennsylvania is in the process of drafting its own.

Two companies doing this work are headquartered in Pennsylvania, Mr. Lowe’s firm found. Another five manufacture gas detection equipment, and there are 38 employee locations of out-of-state firms doing business here.

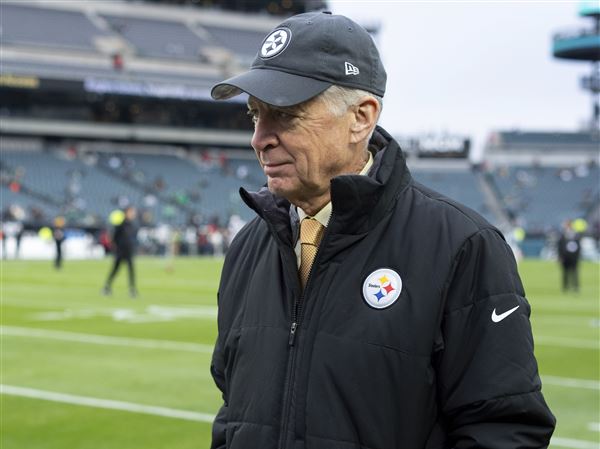

Jack Jarrett, left, a data collection specialist and Winston Chelf, chief pilot, fly by the shuttered Elrama coal-fired power plant along the Monongahela en route to natural gas sites to demonstrate new leak detection technology. (Rebecca Droke/Post-Gazette)

The Environmental Defense Fund has been an advocate for methane regulations, conducting studies that challenge the gas industry’s traditional stance that if there were gas leaking out, it would be in the companies’ own interest not to let salable product dissipate into the air. At the same time, industry trade groups have argued that regulations aimed at limiting emissions would be prohibitively expensive.

In aerial surveys, EDF scientists have found that although most well sites and compressor stations do have their emissions under control, a relatively small bunch of so-called super-emitters ruins the curve for the entire sector.

That’s exactly what Mountain View, Calif.-based Kairos Aerospace looks for when the company is contracted to fly over a large area to sniff out the most egregious leaks. The software outfit rents a small plane and clips a white pod with sensor equipment to one of the wings, then it zooms through the air, covering up to 40,000 acres and 500 well pads in a day.

When a client hired the company to survey that many well pads in the Marcellus Shale region, Kairos located seven large methane leaks, said Laura Yao, head of strategy, speaking at an event sponsored by EDF at the Allegheny County Airport on Tuesday.

So far, that has been Kairo’s only gig in the Marcellus, Ms. Yao said.

“With the regulatory climate, people are holding off,” she said.

Still, business for Chesapeake Bay Helicopters is bustling. The Virginia-based firm that started as a flight school 19 years ago has shifted almost entirely into survey work for utilities and oil and gas firms in recent years.

On Tuesday, pilot Winston Chelf and Jack Jarrett, a data collector, offered rides on a five-seater helicopter equipped with a leak detection system.

The helicopter can pick up methane at a concentration of 0.02 parts per million from as far as 900 feet away. For the demonstration, Mr. Chelf hovered much closer to the ground, passing one EQT well pad after another.

From 200 feet above the earth, gas infrastructure appears as much a part of the topography as the hillsides, homes and industrial plants that dot the southern part of Allegheny County.

A few ducks have found their way into a water impoundment used by oil and gas companies. A wild turkey runs across a field where a pipeline snakes above the ground for a few feet before plunging back down.

Inside the cozy-tight cab, Mr. Jarrett explained how three lines on a computer screen track the air that comes in through a pleated gray tube on the bottom of the helicopter: a red line for methane, green for hydrocarbons and blue for carbon dioxide.

The methane line remained steady as the helicopter passed over an EQT compressor station and headed along the path of a pipeline right of way, where a man walking two dogs looked unsettled under its shadow.

When a leak is detected, the computer makes a series of video game-like beeps. No such sounds were heard above the compressor station on Tuesday.

“That’s a clean site, a very, very nice site,” Mr. Chelf said.

“It’s kind of nice not to get any hits,” Mr. Jarrett said.

A flight survey like this runs about $1,000 an hour, said Matt Eberwine, a project manager with Chesapeake. The company has between 25 and 30 oil and gas clients, he said, mostly pipeline firms.

On Wednesday, for example, the helicopter crew was scheduled to set off for an eagle survey, ferrying a pipeline company biologist along the proposed route of a pipeline to look for nests.

Anya Litvak: alitvak@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1455.

First Published: April 12, 2017, 4:00 a.m.