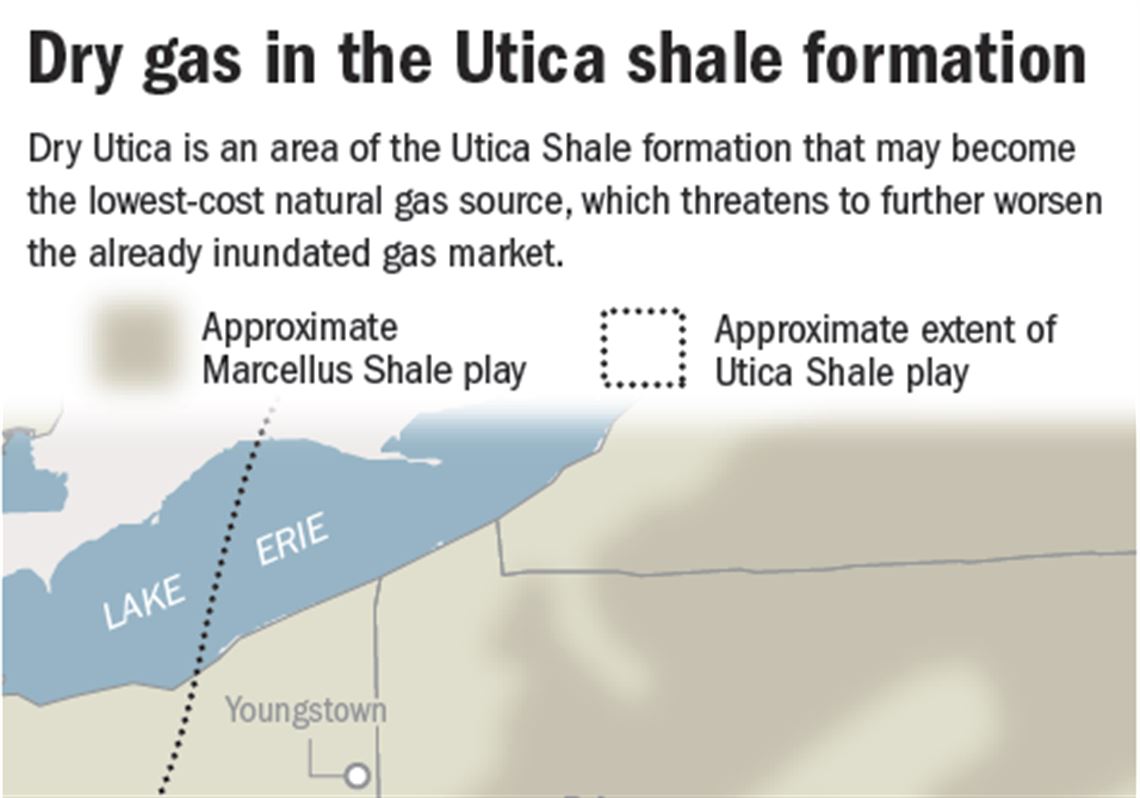

Over the past few weeks, the buzz around the Marcellus Shale has actually been about its deeper neighbor, the Utica, where a handful of companies have drilled record-setting wells for record-high costs.

That has been making some people very nervous — not because the dry portion of the Utica underlying southwestern Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio and the West Virginia Panhandle might be too expensive to drill. Instead, it’s because, as some companies predict, it might soon be the least expensive.

“If there’s a shoe to drop that makes things worse, it’s the dry Utica working,” said Jim Crockard, CEO of the newly-formed Marcellus startup Lola Energy Operating Co.

Mr. Crockard founded Lola this summer with a handful of other former EQT Corp. executives looking to capitalize on good prospects left behind by operators that have had to cut back or vanish because of stubbornly low commodity prices. It’s a been tough market for everyone in the exploration and production business, from startups like Lola to megagiants like Royal Dutch Shell.

The glut of natural gas produced from shale wells over the past five years has inundated the market. Each new shale play seemed to outshine the last, with bigger wells and better economics. The price of natural gas futures at the national benchmark, Henry Hub, dipped below $3 per million British thermal units in January and has stayed there, inching closer to $2 in the past few months.

Now, here comes the Utica, another giant gas field.

The so-called dry portion of the Utica contains methane, the fuel used for heating and cooking. “Wet” portions contain methane as well as other natural gas liquids, including ethane and propane.

“If it does work, if you start flooding the market with economic Utica wells,” Mr. Crockard said, the benchmark price of gas will stay at $2 per million British thermal units.

More to the point: “It will wipe out all the economic Marcellus wells.”

In July, Erika Coombs, senior energy analyst for Colorado-based BTU Analytics, predicted the success of the dry Utica — defined as the area becoming the lowest-cost source per molecule of natural gas — would be the death of the Haynesville Shale in Louisiana, which has been hanging by a thread since the Marcellus stole its thunder.

“The last thing the market needs is another gas play as prolific as the Marcellus Shale,” she wrote at the time.

All the excitement and panic over the dry Utica is based on a lot of “ifs.”

If the companies can get their costs down from $30 million to around $13 million per well, and if all wells perform like EQT’s breakout Utica well in Greene County, Ms. Coombs said the Utica could disrupt the national market for gas in a few years’ time.

But there have been fewer than 100 of these wells drilled in the tri-state area so far, and only a dozen or so have been publicized.

“The dry Utica is still in the early innings and maybe you have some people rooting for it and some people rooting against it,” said Matt Hoza, also an analyst at BTU Analytics. “It’s a little too early to start getting really nervous about it.”

Beyond the Appalachian Basin

The Utica’s impact will reverberate beyond the Appalachian Basin, analysts warned.

“In general, if you find more stuff, prices are going to be lower,” said Rusty Braziel, president and principal energy markets consultant for RBN Energy in Houston.

But it’s more complicated than that.

For more than a year, the Marcellus and Utica have been so productive that the pipelines available to ship it to other markets haven’t been able to keep pace. That has left Appalachian producers selling at a discount to other trading points and, crucially, below the national benchmark at Louisiana’s Henry Hub.

A record number of new pipeline projects have been announced to de-bottleneck the region, with many headed for the Gulf Coast. And while that might relieve the disadvantage that Marcellus and Utica producers face, it will also deliver a gush of cheap gas to Henry Hub, driving down the national benchmark price lower for longer, Mr. Braziel said.

For the better part of a year, producers have been confiding in Mr. Braziel about the potential of the dry Utica, which makes them both excited and nervous, he said.

Some worry that if the Utica works, it may push down the overall price of gas that would be needed for profitable development. Tim Dugan, Consol Energy Inc.’s COO of exploration and production, said he’s not concerned — not because it won’t happen but because his company can lean on the Utica if it does. In fact, Consol said its focus over the next several years will shift to the dry Utica.

“Logic indicates that Utica development will displace other higher cost developments and not be additive,” he told investors last month.

But there’s more at play than logic.

Producers like to produce

There are many reasons why oil and gas companies continue to drill wells and grow production when it seems counter to their interests.

Some may have leases that would soon expire if not secured by a producing well. Some have loan covenants and joint venture agreements requiring a certain level of activity and reserves. Some simply have bills to pay and cutting production means cutting revenue.

Plus, investors like growth.

“(Exploration and production) companies are typically rewarded for production and finding new plays,” Ms. Coombs said. “From a market perspective, that’s terrible.”

Even if the dry Utica works and depresses the overall breakeven price for gas wells, there are still plenty of economic Marcellus wells that could be drilled, according to Ms. Coombs.

She estimates that in northeastern Pennsylvania, 1,200 wells were drilled through 2014 that made money with gas prices below $2/Btu. But there are another 3,000 locations where such wells haven’t been drilled yet, she said.

That means even if producers were drilling solely on the economics, supply would remain robust.

Perhaps the most detailed discussion of the Utica’s impact over the past few weeks came from Dave Porges, the CEO of EQT.

“If the Utica does work,” he told analysts last month, “some of our other inventory that requires higher prices to make economic returns would be deferred possibly for many years.

“The cannibalization of other opportunities will affect everyone including those of us who will be much better off if the deep Utica play does work economically,” he said.

Anya Litvak: alitvak@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1455.

First Published: November 9, 2015, 5:00 a.m.