Since forever, it seems, people have come to Master’s Hardware in Swissvale looking for something.

Soon, they will be looking elsewhere for a hardware store.

After 36 years on Roslyn Street, owner Stan Master is closing his hardware store for good on Dec. 16. It’s the last of what once were three stores of its kind in the 1.2-square-mile borough overlooking the Monongahela River valley, about 9 miles east of Pittsburgh.

Everything in the store went on sale in late November, and Mr. Master said he will spend the last weeks of December packing up what’s left — paint brushes, bolts, lamp oil, Fumeless brand drain opener.

Out back in the garage, handwritten signs taped to a forklift and pipe threading machine in the cellar say they’ve already been sold.

The building owner dropped by in August to say that he wasn’t renewing the lease.

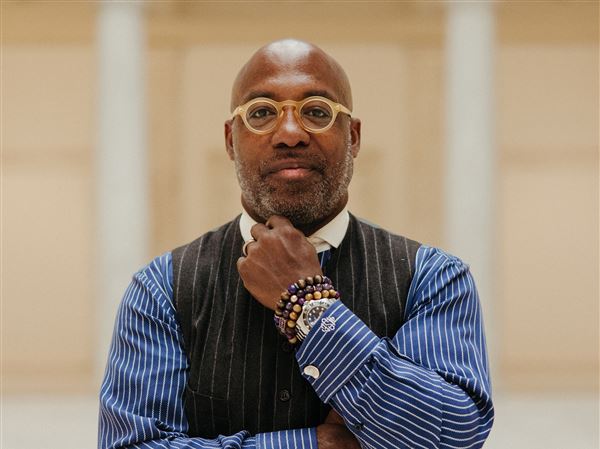

“How much longer are you planning on working?” the landlord asked Mr. Master, a trim, compact man, 76 years old, who favors flannel shirts and blue Dickies brand work pants.

“I told him at least a couple more years, anyway.”

No, the landlord said, “We got other plans for the building.”

Mr. Master, who lives in Plum, said he’s fortunate to have been able to hold on until the end of the year. January would’ve marked 37 years running the store 9-to-5, six days a week, except holidays.

He said he has no plans right now for when the store is shuttered.

Diana Wilhelm, of Braddock Hills, recently dropped by the hardware store, which is located in a fading neighborhood of churches, hamburger joints and gas stations. A bell tinkled with the opening of the door, the wood floor creaking as she walked inside.

Ms. Wilhelm said she needed some tiny wood screws.

But the store closing was very much on her mind.

“It hurts my heart,” said Ms. Wilhelm, 62, who works in a medical clinic and used to live in Swissvale. “It does. It really does.”

Dave McFarland, a 46-year-old truck driver, who lives in Elizabeth, has been coming into the hardware store since he was 10 years old and lived a few streets away. His grandmother used to send him there on errands, Mr. McFarland said.

“He’s been here about my entire life,” Mr. McFarland said of the store owner. “I just had to come in. I just had to come in and at least tell you congratulations.”

Mr. Master, who enlisted in the Air Force during the Vietnam War and served as a crew chief on one of those big C-130 cargo transport planes, was working at the Volkswagen assembly plant in New Stanton when he saw that the hardware store was for sale.

The car plant shut down in 1988.

For several years before it closed, though, he’d work morning shifts wrestling fenders into place on Rabbit cars and trucks. He then would spend afternoons working at the store.

“You know, I’m going to buy this store,” he told the owner.

Before Ikea home furnishings, Master’s Hardware rewired table lamps and fixed vacuum cleaners — that is until sweepers began using electronic parts. The store sold paint and primer before it came already mixed in the same can, but Mr. Master said you still get a better finish with separate coats of each.

There was a time when the garage in the back of the building was stacked to the ceiling with bags of concrete, the store selling out every year. But that was before the surge in concrete mixing plants and trucks that delivered wet product right to the job site, Mr. Master said.

A letter Mr. Master hands to customers about the store closing is signed “with sincere and heartfelt appreciation.” Serving “the Swissvale and surrounding communities has been a pleasure we will never forget.”

Threading black iron pipe to custom lengths was once a big deal, he said. Not so much in the past 10 years.

“The draw isn’t there for all of these things,” he said. “You can’t sell it if nobody’s going to buy it.”

In the back of the store is a big iron scale once used to weigh nails when they were still sold by the pound. But even the use of nails isn’t what it was.

“Nails don’t sell the way they used to,” he said. “Everybody uses the screw guns anymore.”

The store will continue selling custom-cut window pane glass and fixing screen doors and windows right up until the end. And pegboard-lined aisles will feature bolts and extension cords along with cleaning products — Windex, Mop & Glo and boxes of Brillo, marketed as the original soap pad — just like offerings at the big home improvement centers.

Despite the obituaries over the years, hardware stores are not dead. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a spike in growth as homeowners took a new interest in do-it-yourself projects, growth that has continued.

In 2022, the U.S. consumer hardware market grew 7.1% to $19.6 billion, with only 20% of orders made online, according to the nonprofit Home Improvement Research Institute in Indianapolis, Ind.

Many people still prefer the personal touch of hardware stores over big box competitors. Mr. Master’s wife Donna, 70, for example, used to come by during the holidays every year to trim the storefront windows with tinsel and Christmas lights, a job that was later taken over by Ray Seiler, 72, an employee for 34 years.

A letter Mr. Master hands to customers about the store closing is signed “with sincere and heartfelt appreciation.” Serving “the Swissvale and surrounding communities has been a pleasure we will never forget,” the letter said.

As for those big box competitors, Mr. Master said he once asked a Home Depot clerk to find a particular item — he’s forgotten what it was now — but left without it, frustrated.

The clerk had directed him “over there in the middle aisle,” Mr. Master said. “There were 10 middle aisles!”

“This is sad, sad, sad,” said Diana Wilhelm of Braddock Hills, following Stan Master to a counter at the back of the store. He shrugged off the comment, focusing instead on the box of tiny screws he’d started picking through.

The story of Master’s Hardware is very much the story of the borough it calls home and dozens of other small Western Pennsylvania towns that sizzled with prosperity and promise before starting a long, slow fade. Swissvale’s population of 8,392 — propped up for years by railroad signaling maker Union Switch & Signal — is half its peak population of 16,488.

The population peak came in 1950.

Union Switch employed more than 4,200 people in the early 1970s but closed in 1985 and was demolished a year later. The 40-acre tract was redeveloped into a shopping plaza, home now to a supermarket, liquor store and clinic that pays for blood plasma, $1,000 for eight donations.

Back at the store, Ms. Wilhelm, is looking for wood screws but still worried about the closing.

“This is sad, sad, sad,” she said, following Mr. Master to a counter at the back of the store.

He shrugged off the comment, focusing instead on the box of tiny screws he’d started picking through.

“We’ll see what we can do,” he said. “Is that metric?”

“It’s from a home entertainment center,” Ms. Wilhelm said. “I need four.”

“I only have two,” Mr. Master said, “but that’ll get you started.”

“That’s 59 cents,” he said, counting out change. “And I thank you much.”

Kris B. Mamula: kmamula@post-gazette.com

First Published: December 9, 2023, 10:30 a.m.

Updated: December 11, 2023, 6:05 p.m.