Dilip Kumar, aka Yousuf Khan, a Bollywood legend and a humanitarian par excellence, died July 7 in Mumbai, India, at age 98. He was given a state funeral by his home state of Maharashtra.

His overarching presence in Indian cinema spanned more than half a century. While most actors and artists fade away after retirement from the profession, Kumar remained a praiseworthy presence in the hearts of his billions of fans in India, Pakistan and in the Urdu/Hindi diaspora.

I grew up in Peshawar hearing the stories of Dilip Kumar and seeing him in movies. Each of his films resonated with people across India and Pakistan, but more so in Peshawar, the city of his birth. His on-screen demeanor, his inflections and his dress and hairstyle became a trend for millions of his fans. We Peshawaris felt a close kinship with him.

He was born in 1922 within the walled city of Peshawar into a large family of 12. His father, Ghulam Sarwar Khan, supplied seasonal fruits from Peshawar to the British Indian Army as far away as Calcutta. In 1928, his father went to Mumbai to expand his business. Soon, trainloads of semi-ripened Peshawar fruit started traveling across India to the British garrisons. However, it all came to stop when British India joined World War II. The family fell on hard times, forcing young Yousuf to seek work to help support the large family.

At age 18 he left home for Poona (now Pune) and worked in the British Club, where he sold sandwiches and fruit to the English sahibs and their wives. He made good money and returned home with savings of 10,000 rupees. His mother was curious about the large sum of money, but the son assured her he had earned the money working very hard at the British Club.

While looking for a job in Mumbai, he was sent to film star Devika Rani, who owned with her husband a film production studio called Bombay Talkies. She was impressed by the young man’s looks and demeanor and hired him at a princely sum of 1,250 rupees per month. Because he had good command of the Urdu language, he was to work as a script writer and an actor. Rani also suggested he adopt Dilip Kumar as his movie name. His first movie, “Jawar Bhata” was filmed at Bombay Talkies. After that, there was no looking back for the young man.

For more than half a century he dominated Indian cinema, acting in more than 70 films, including a large number of box office hits, and garnering seven Film Fare Awards (the Indian version of the Oscars).

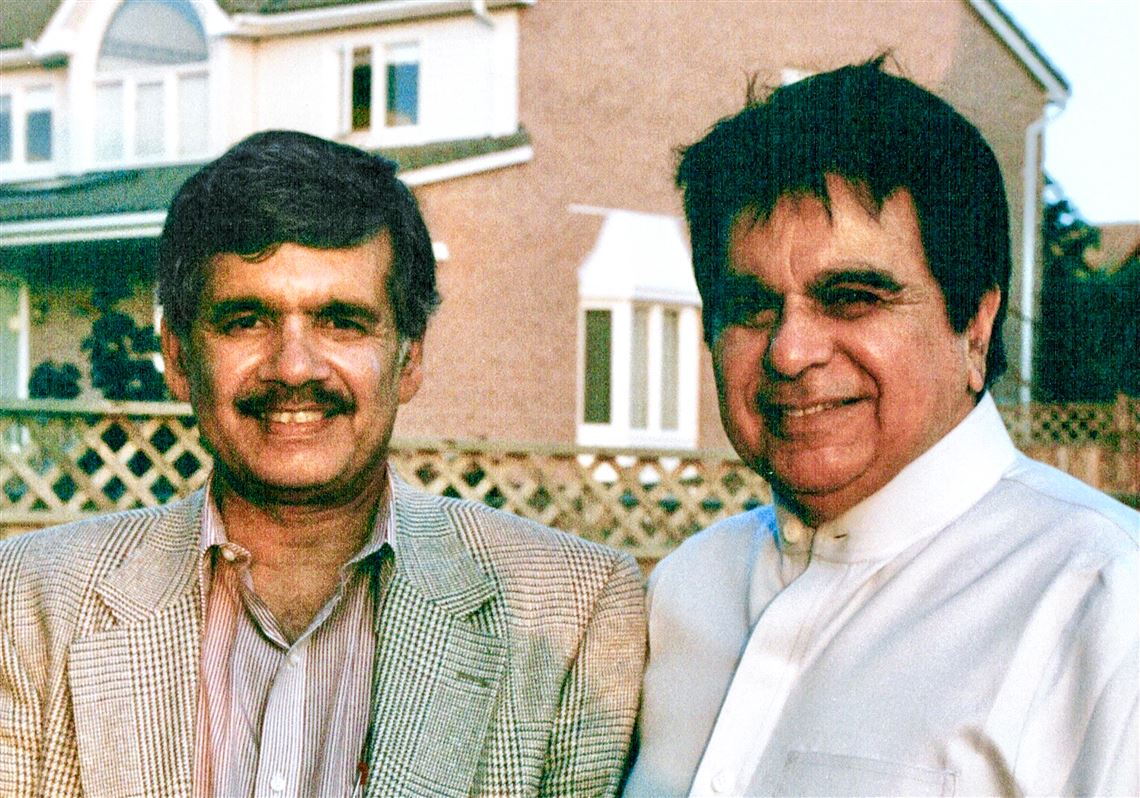

Since my college days, I had wished to meet him someday. My wish came true in June 1993 when Dr. Abida Usman, his grandniece from Toronto, invited me for an afternoon of conversation with him.

I found him to be extremely gracious and warm. At age 70, he looked youthful, healthy and cheerful with the slightly ruffled jet-black hair that was his trademark. We spoke in Hindko, our shared mother tongue.

I gave him a copy of my hand-drawn map of the old walled city of Peshawar and a monograph on the history of the city. He was excited to see the map and took his time tracing his finger across various neighborhoods and finally the location of his ancestral home. That map was later included in Sanjit Narwekar’s 2012 book, “Dilip Kumar: The Last Emperor.”

After pleasantries I asked him what he remembered about his youth in Peshawar. He said that perhaps the only significant part of his life was his childhood in Peshawar. To my surprise, he brushed off his myriad accomplishments as an actor, philanthropist and community leader.

Although he had arrived just a day earlier from India and must have been feeling jet lag, he sat down to rounds of tea and conversation with his family and me. He was certainly in a mood to talk.

Crossfire

On April 23, 1930, there was a huge demonstration against British rule in Peshawar. Tens of thousands of people gathered in the Street of Storytellers, the main bazaar. Eight-year-old Yousuf wandered from his home to the bazaar to witness the commotion. The situation soon deteriorated, and police opened fire on the crowd. When bullets started flying, he ducked under a storefront with “my one foot in the gutter and the other foot on the pavement,” he said.

A native policeman pulled him out, gave him a not-too-gentle slap on the neck and told him to get lost. Yousuf ran for his life, taking the back alleys to reach home, only to be scolded by his father. That day, hundreds of people lay dead in the bazaar. A stray bullet could have easily killed the future matinee idol.

His father was deeply steeped in Peshawari culture. When Prithivi Raj Kapoor, the son of his good friend from Peshawar, started working in movies, Sarwar Khan told his friend not to allow his son to work as an actor. He considered such work good only for lower-class people.

“Little my father knew,” said the movie icon, “that his own son had also become an actor.”

When I asked him if his father eventually accepted him as an actor, he said, “No, he never did.” He was visibly pained and had moist eyes when he said this.

Inner conflict

In the beginning, by adopting a screen name, he could hide his budding acting career from his father. But as his face and name became common in Mumbai, the smoke screen dissipated. People would show up at the family home wanting to see Dilip Kumar. He would leave through a back door. He would tell his fans he was not the character they saw on the screen. It took him a long time to get comfortable with dual identities.

He was known as a method actor in the tradition of the Russian theater practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski, who believed in total immersion in a character. The ambiguity between the real person and the characters he portrayed stayed with Kumar and necessitated sporadic psychiatric therapy, he told me.

The family returned to Peshawar from Mumbai every year during the summer months to keep in touch with their extended family. These visits reinforced Yousuf’s love for the city. He was caught in the police melee during one of those visits. The family continued to visit Peshawar until the partition and independence of India in 1947. The visits ceased because Peshawar was now in Pakistan.

Disillusionment

Kumar was an ardent believer in and supporter of Indian secularism as espoused by Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru. He took an active part in political campaigning for Indian Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru and later his daughter, Indira Gandhi. Disappointment came early. He was labeled a spy for Pakistan and had a case registered against him. He knew Nehru personally and met with him, but except for sympathizing with him, he did nothing.

The case was eventually dropped, but he remained the target of Hindu nationalists until the very end. While he had advocated for Indian secularism most of his life, he later abandoned that philosophy.

He started identifying himself as a Muslim, and devoted his efforts to education for Muslim girls and boys. During my 1993 visit to his grandniece’s home in Toronto, another visitor was discussing with him an ambitious project to open schools for Muslim children in India.

In 1998, the Pakistani government bestowed on him its highest civilian award, Nishan-e-Imtiaz. The militant Hindu organization Shiv Sena and its firebrand founder, Bal Thackery, demanded Kumar either return the award or move to Pakistan. He met Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and asked if he should return the award. The prime minister, to his credit, said it would have to be his decision and not that of the Indian government. He kept the award.

He is the only person who has received the high civilian awards of both India and Pakistan. India conferred on him Padma Bhushan, its third-highest civilian award, in 1991 and in 2013 its second-highest award of Padma Vibhushan.

Childhood memories

Henry Troyat, the Russian-French writer, has said that childhood experiences are always the most important in our lives. Those memories are the building blocks of our personalities. Looking at the fascinating life of Dilip Kumar, it is apparent he kept those memories and Peshawari traits close to his heart.

One of those traits was hospitality. There were stories about Peshawaris showing up at his door and his welcoming and entertaining them.

It remains surprising that most of his biographers have skipped over his childhood, given that he had said that it was the most important part of his life. I asked him if he had considered having an account of his childhood documented. He said someone was going to work on the project, but had not done anything yet.

Kumar shared that he was under tremendous pressure. Two of his movies had been held up by India’s censor board for the flimsiest of reasons. He asked me to pray for his health so he could accomplish the things he wanted to do.

After spending three hours, I begged his leave. He got up and thanked me for the flowers I had brought as well as the map of Peshawar. He gave me a hug and said in Hindko, “May God be with you, and may you always have light in front of your face.”

S. Amjad Hussain is a columnist for the Toledo Blade and an emeritus professor of surgery and humanities at the University of Toledo. Contact him at aghaji3@icloud.com.

First Published: August 23, 2021, 10:00 a.m.