Not everything was glittering in the so-called Golden Age of comics, nor did all become sterling with its Silver Age.

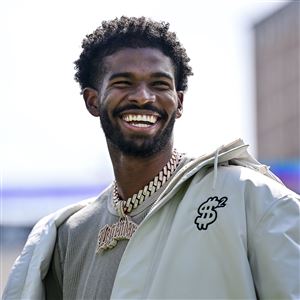

That’s one part of the message filmmaker, DJ and passionate high-profile comic book collector Phillip Thompson, 52, looked to get across as he recalled the story of a 1965 comic series called “Lobo” — not the DC Comics version, but a Dell Comics Western — the first time a Black character carried a comic book title alone.

“They only did two issues, and the first issue had Lobo standing on the cover with a gun,” explained the Penn Hills resident. “White distributors saw that book and they ripped that [expletive] up. They said, ‘Yeah, we're not doing this.’”

But, as evidenced in Thompson’s collection of 200 pieces of original artwork, photographs, rare comic books and memorabilia either made by Black artists, focusing on Black characters, or coming from Black collections from 1941 up through today, neither the unceremonious demise of “Lobo” or other social and industry hurdles stopped a procession of Black artists, writers, superheroes and enthusiasts from making meaningful contributions to the genre throughout its history.

After ambitious efforts and ample mileage logged toward its assembly, Thompson’s “Collections in Black” is now on display at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center through Jan. 12 as part of an exhibit that also features the abridged version of his original documentary of the same name.

“It was funny because a lot of Black artists in the beginning were able to get work because you would send your work in. Sometimes you didn't go to the office,” Thompson said, recalling the story relayed to him by Black comic artist Brian Stelfreeze. “They didn't know you were Black.”

“And then, when they found out that he was Black, all of a sudden it’s ‘We want you to do a lot of the Black books.’”

Among the collection’s chief protagonists is Thompson’s favorite creator, Pittsburgher and Westinghouse High alum Matt Baker, a legendary artist long enshrined in the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame, who saw his heyday during the Golden Age, from 1938 to 1956.

“When you look at the Golden Age comics, there's a distinct style that you can look at and you say, ‘Oh, this is old.’ You look at some of Matt Baker's covers, and they still look good,” Thompson said.

“Back then if they knew who you were, especially during the Golden Age, it was nearly impossible to get a job,” Thompson said. “But Matt Baker was so good that, in spite of the racism and whatever, he was so dope with it that they had to go, ‘Look, this Baker guy is phenomenal.’ And there was no choice.”

Assemble!

Thompson’s collection was assembled over the years through his own extensive holdings, his personal connections with many of the artists and the Carnegie Library of Downtown’s own Creating a Community collection.

“I have all the original pages, the original artwork to the very first time a Black man was presented positively on the cover of the book and featured on the inside,” said Thompson. “I own those pages, not Joe Louis, not the Smithsonian, not some billionaire hedge fund super collector. I have them....This has never been done before, an exhibit based on all Black comic art where all of it is original pieces.”

In acquiring them, Thompson would find himself places like New York, eating breakfast with iconic Uncanny X-Men artist Larry Stroman as he drew a commission of Storm. Then there was Detroit, with Misty Knight creator Arvell Jones, among other rendezvous.

“Those [artists] are on speed dial. I talk to these cats every other day,” he said.

But even now, it’s been a surreal journey.

“To be able to have your heroes as your peers is a dope feeling,” he said.

History meets art

The expansive collection also features the work of Pittsburgher Jackie Ormes, who became the first nationally published African American woman cartoonist after rising to prominence through her work at the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the leading Black newspapers in the U.S., in 1937.

“Collecting preserves history, and that is one of the important pieces of collecting, is the ability to preserve history,” Thompson said. “And for me to have some of these pieces in my collection means that that history won't be forgotten.”

“I think the most important thing for me is for people to get the history right. History is important, and a lot of times, history is shaped by those who tell it. And a lot of people who are these historians sometimes have a bias. Black or white, good or bad, there’s a bias. I just want be authentic and as open and honest as possible.”

Thompson also emphasizes the exhibit’s inherent ability to inspire absent labels.

“I'm big on inclusion without exclusion. This isn't an exhibit just for Black collectors or just for the African American community,” he said. “If you're a comic book collector, you're going to love what's in in the exhibit.… I want you to get out of it what you want to get out of it, and what you need out of it.

“You’re going to learn something, but at the end of the day it’s about the artwork.…These artists are legitimized in in the comic world, but I want people outside of the comic world to sit back and look at this fine art and say, ‘Oh, this is incredible,’ because some of this [expletive] need museums.

“I know art is subjective, but I feel like a lot of these comic artists do not get their just due outside of their medium and their culture.”

Bookman Begins

Thompson’s origin story saw him take the first steps on the path to collecting at an early age.

He’s the son of two HBCU graduates, his mom a history teacher and later a principal at Penn Hills. (Thompson himself later attended the HBCU, Rust College.) And his father maintained his own comic book collection full of titles like Black Panther, Spider-Man, Master of Kung Fu and others.

“Me and my brothers would sneak in, and we would read his Black Panther comics,” Thompson remembered with a smile. “That was dangerous territory doing something like that, literally and figuratively.”

Black Panther, The Falcon, Storm, Luke Cage and a slew of other characters he discovered as he became a more devoted collector later on were a constant presence in his life. But Thompson says his “heroes were at home.”

“I’m going to dispel this myth real quick, and a lot of people are not going to like this,” he said. “Every kid wants to be Batman at some particular point. Every kid jumps off the couch with the cape on and they're Superman, Black, white, whatever. Male or female. Everybody wants to be the Hulk. With Spider-Man, for instance, every kid gravitates with Spider-Man because he's young and he has issues and he has problems. Those are universal. Everybody gets that. Little kids love the Hulk because kids like to tear up [expletive].”

In his early 20s, Thompson’s focus expanded beyond simply seeking out work by his favorite artists like Baker, Billy Graham, John Burns and Frank Miller when he discovered an issue of a Lois Lane comic where she becomes a Black woman for a day. He grabbed every copy of it he could find.

“Then I had a moment where I just started collecting firsts, once I started getting serious about my collecting. First appearance, first this, first that. Then I started saying, ‘OK, who was the first Black character here?’ Then I started collecting Black moments, Black artists, Black writers and things of that nature,” he said. “So it's just kind of evolved.”

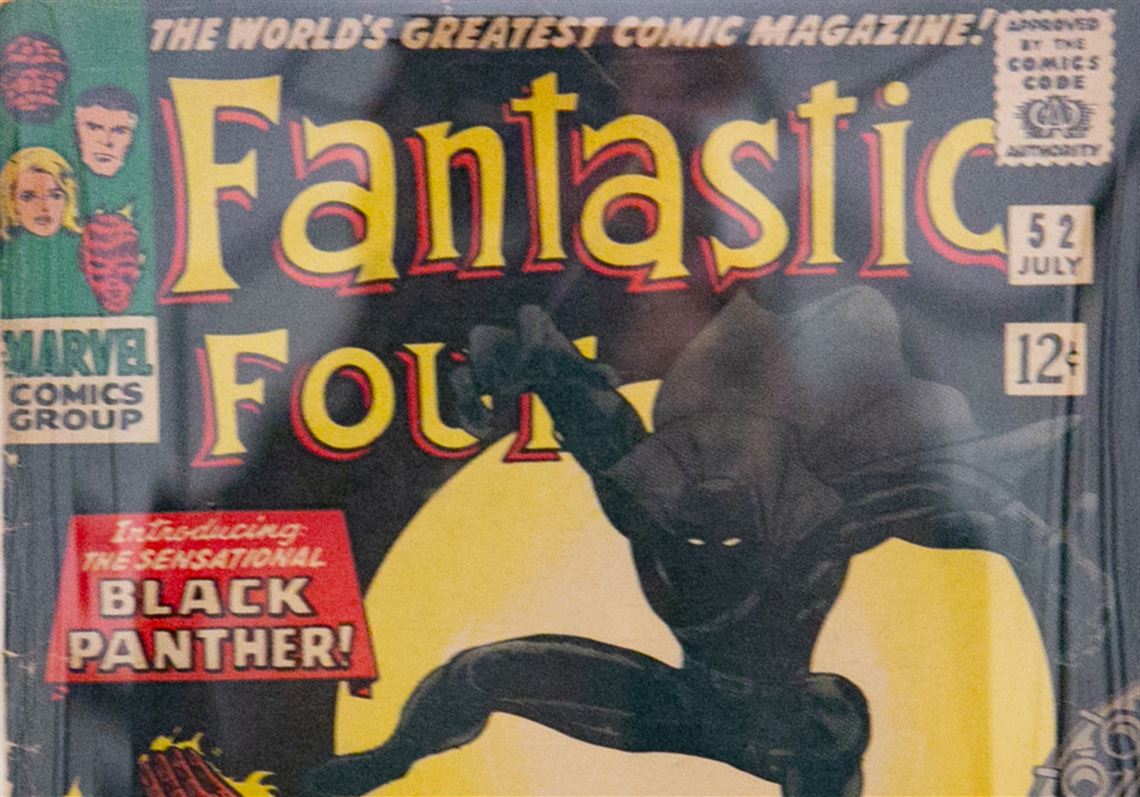

It was the same for titles like Fantastic Four No. 52, the first appearance of Black Panther.

“I was just grabbing them like hotcakes,” he said.

As his collection grew, so did his presence within the community.

“The next thing you know I'm in a private group of Black collectors where that's pretty much all we do is share what we have and throw each other alley oops and help each other out in our collecting endeavors,” said Thompson. “I’ve been able to get these alley oops and slam dunk them, and then sometimes give the ball back to whoever needs it.”

First Published: August 26, 2024, 9:30 a.m.

Updated: August 26, 2024, 6:40 p.m.