Bound in marbled calfskin, long red rows of books filled Marie Antoinette’s grand library behind gold-lined vitrines — so shimmering and abundant they almost looked fake.

And they were. Faux book spines hid in door panels above her metal-plated logo: a loopy “M” embracing a narrow “A.” While the rest of her Versailles library featured books on theater and theology, music and Molière, a corner facade of mock jackets revealed the 18th century French queen’s desire to brandish the aesthetics of intelligence.

Collecting books for show is not a new trend.

But social media consumerist culture has brought on a new manifestation of the age-old habit.

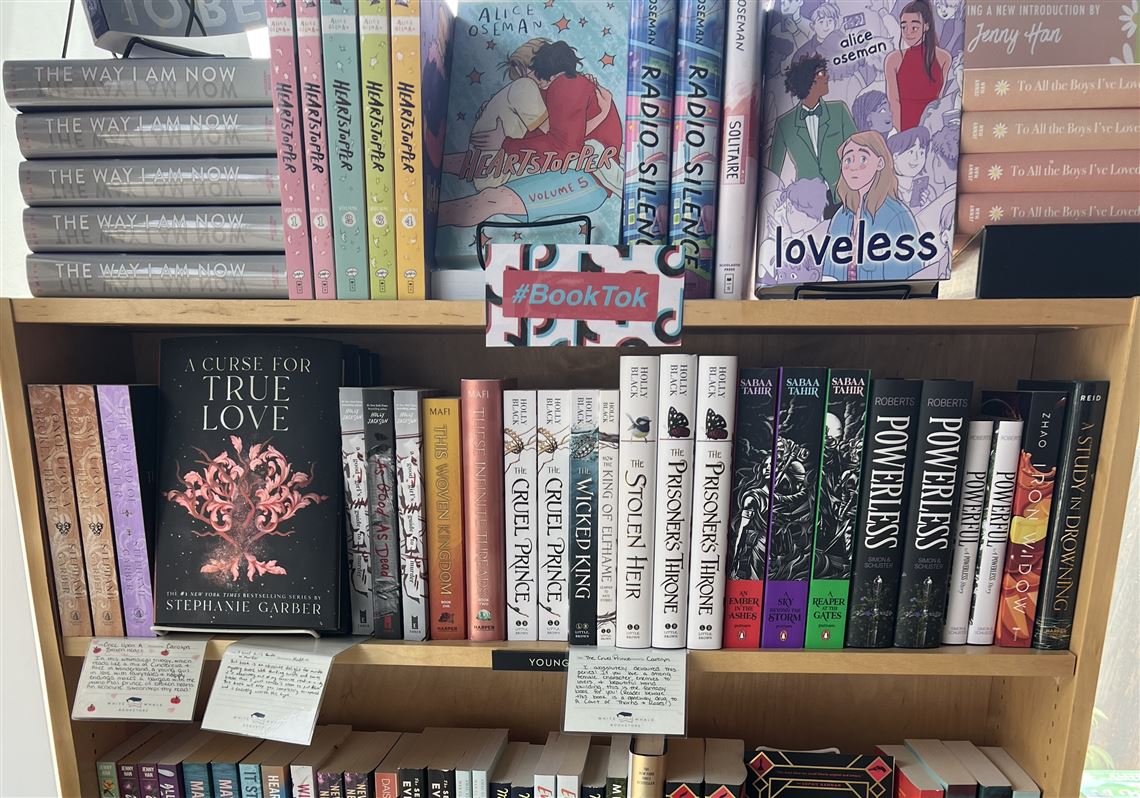

On BookTok, a TikTok community whose hashtag has garnered over 280 billion views, influencers share reviews and recommendations before color- or genre-coded bookshelves that might contain several editions of the same novel. Users unbox 10-volume fantasy series, flex their weekly book-buying spree or race through short reads to reach their 200-book goodreads goal. BookTok seems intent to epitomize overconsumption: read more, collect more, own more.

“I think that people collecting books because they have sprayed edges and new covers isn't exactly the same thing as buying the book because they like to read it,” said Adlai Yeomans, owner of Bloomfield’s White Whale Bookstore. “But it's never a bad thing for people to get excited about books.”

Even if reading is growing into a consumerist obsession, not everyone is ready to decry a democratization of literature. More people are picking up books, whether those are hefty classics or breezy beach reads.

But alongside the rise in book consumption, the question of content becomes central, and a new online discourse has emerged regarding the merits of popular social media books with fluffy, fantastical or sexual themes.

Of BookTok and yellowbacks

White Whale Books displays internet-trending reads on a #BookTok shelf. Mr. Yeomans said that sales of viral genres like romance, fantasy and romantasy — a portmanteau of the two present in books like Rebecca Yarros’s “Fourth Wing” and Lauren Roberts’s “Powerless” — have grown in recent years. Romantasy books might feature a darkly handsome prince, a snarky sword-wielding teenage girl, sworn enemies that fall for each other and dragons or faeries.

Industry research firm Circana reported that the genre has “a lot of fuel” this year. As of late July, five books on their list of this year’s top 10 selling books fit beneath the romantasy umbrella.

But not everyone is happy about these public-appealing reads. A college newspaper headline charges: “BookTok is ruining books.” One TikTok account, dedicated to slamming BookTok-popular novels, features comments like “what actually happened with literature” and “booktok books … take art out of literature.”

Yet it’s hardly new.

This contemporary fad, and the hostility that surrounds it, seems to be a modern articulation of a historical pattern. In the 1840s, “yellowbacks” shattered the reading landscape — early, cheap, machine-produced books bound in yellow paper.

A digitized UCLA collection displays their covers, which might illustrate the novel’s climactic scene: a man plummeting from a hot air balloon, a couple with little distance between their lips, a woman looping a lasso on horseback. The books were sensational, meant to entertain.

Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Library holds the country’s second-largest assortment of yellowback books. Librarian David Faulds is an expert on the collection.

“The demand came not just from the lower cost of books but also the social changes that occurred during the 19th century,” Mr. Faulds wrote on their webpage Yellowbacks at Emory. “The industrial revolution saw a concentration of the population in cities like London and Manchester, a growing middle class and higher literacy rates.”

‘The beauty of the books’

In the 19th century, mass production was the accessibility vehicle. Now, it’s convenient vendors like Amazon. Social changes to Victorian society are likened to our contemporary social media craze, with new readers clustering then in metropolitan cities and now in the highly-populated virtual city of TikTok. And historically, like today, intellectual readers are dismissive of these ‘lowbrow’ inventions.

But today, yellowbacks are important artifacts. They symbolize a growing literate public and an excitement around reading.

“People who came out of those, you know, ‘trashy’ genres, some of them are now classics,” said M.C. Benner Dixon, PhD, a Pittsburgh-based scholar, novelist, short-story writer, essayist and poet who also coaches and edits.

She wrote her dissertation on Mark Twain. “We really venerate some of the patterns and the tools he's pulling from these kinds of, jokey, ‘low class’ styles of writing,” she said.

With experience in the world of small presses and as a voracious reader, she refused to declare any book elite or superior to another.

“Some days I want something that is just sweetness in my mouth, and then other days I want to chew on something hard,” Ms. Benner Dixon said. “I don't have too much anxiety about fads in books coming and going because, you know, people are complex and complicated and they're not — the reading public is not a monolith.”

Like the striking yellowback covers, eye-catching visuals — illustrated edges and swirly, colorful jacket designs — are all the rage. But the practice of book collecting perhaps necessitates a reframing to see more than frivolity in these patterns.

“The beauty of the books is real, right,” Ms. Benner Dixon said. “The work that's happening on covers — there are artists and people pouring their hearts into that as well.”

The chemistry of reading

Fueled by new vehicles like Amazon, people can acquire these new books with a click.

And somehow, bookstores have managed to hold their own.

At White Whale Books on a recent Sunday, readers populated the cozy aisles and adjoining café, debating feminist fiction and divulging their own story ideas above cracked-open spines. The independent store remains an intellectual hub.

“The only thing that Amazon can do better than an independent bookstore is offer a lower price point,” Mr. Yeomans said.

White Whale’s curated selection, its physical space and its facilitated human connection are elements with which an online vendor cannot compete, he said.

Literary professionals agree that reading is not in peril. Spaces for booklovers seem to be thriving more than ever. New styles and genres are accessing new audiences. People love the aesthetics of book collecting, as Marie Antoinette did, and they love trendy, accessible reads, as the Victorian public did, they maintain.

“We need the full breadth of it because they push against each other. They challenge each other,” Ms. Benner Dixon said. “They give us new forms that we didn’t have before, and I love that. I’m excited about that chemistry.”

Hudson Warm is a business writing intern at the Post-Gazette, a student at Yale and a Scholastic and National Indie Excellence Award-winning author of two novels: hwarm@post-gazette.com.

First Published: August 5, 2024, 9:30 a.m.

Updated: August 6, 2024, 7:56 p.m.