As a boy, William R. Huber saw the name of George Westinghouse all over his native Pittsburgh, on a monumental bridge over the Turtle Creek Valley and various buildings.

Huber, a retired electrical engineer who worked for Bell Laboratories, is the author of a concise, excellent biography of Westinghouse, the eminent entrepreneur and innovative inventor who received 361 patents and founded more than 60 businesses. Two of them – Westinghouse Air Brake and Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing, were Fortune 500 companies.

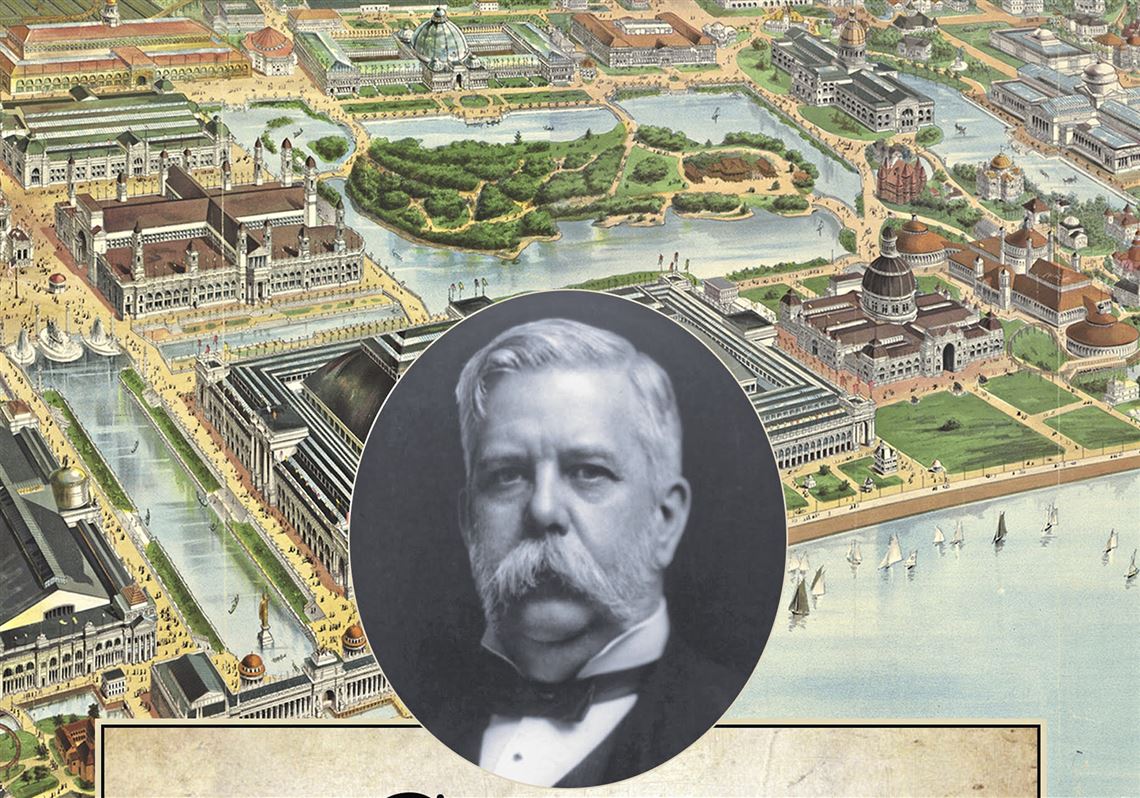

The cover of “George Westinghouse: Powering The World” hints at its focus, with Westinghouse’s face imposed on a colorful view of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Aided by the brilliant and eccentric inventor Nikola Tesla, a Serbian-American who built the first alternating current motor, Westinghouse demonstrated the safety of alternating electrical current by using it to light the 1893 World’s Fair.

McFarland Press ($39.95)

“Powering the World” is filled with evocative pictures, maps and detailed diagrams that show how Westinghouse’s inventions work and illuminate the man’s fertile imagination, fortitude and powers of concentration. Huber unfolds a richly textured story about how one man’s persistence almost invariably paved a successful path to solving daunting problems.

Westinghouse is a difficult subject because he avoided publicity while he was alive and burned all of his papers before he died in 1914. The first two biographies were published in 1918 and 1920 and a more recent 2007 book is a bit dry. To this reviewer, a 278-page biography is preferable to a 1,000-page volume.

Huber details how young George worked hard in his father’s successful machine shop that made farm equipment, including threshers. In Schenectady, N.Y., young George tinkered diligently, endlessly, tirelessly. His father, a demanding and disapproving figure, did not want his son to become a mechanic.

Textbooks bored young George, and he was a poor student partly because he often skipped school; he wanted to work instead on mechanical projects that fascinated him. At age 19, he received his first patent for a rotary steam engine. After three months at Union College, Westinghouse dropped out, making this an inspiring text for anyone who lacks formal education but dreams of starting their own business.

In 1869, Westinghouse made his reputation and fortune by inventing and patenting the straight air brake, revolutionizing rail transportation and making it safer for railroad employees, commercial shippers and passengers. Before this invention, passengers sometimes died in horrific crashes and hundreds of railway employees were either killed or crippled in their efforts to stop moving trains with hand brakes or other primitive methods. Then, he improved on his invention with the automatic air brake.

After moving to Pittsburgh in 1868, Westinghouse and his devoted wife, Marguerite, initially lived in Allegheny City, now the North Side. On April 30, 1871, he took her on a carriage ride to the East End and presented her with a birthday gift – a three-story brick mansion called Solitude. Surrounded by roses, hydrangeas and stately trees, the home stood on land now known as Westinghouse Park in North Point Breeze.

President William McKinley, Britain’s Lord Kelvin and European monarchs dined at Solitude. So many notable people visited that a more fitting name for the mansion would have been the Wayside Manor for Traveling Dignitaries and Engineers.

For his convenience, privacy and to avoid Pittsburgh’s damp winters, Westinghouse had a secret, 220-foot-long underground tunnel built to connect Solitude with his workshop. The tunnel still exists. The mansion was strategically located near a Pennsylvania Railroad line so that he could travel quickly aboard the Glen Eyre, his private rail coach.

Westinghouse played poker with his famous neighbors, Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, and like them, he was all about business. He also possessed a keen eye for spotting and recruiting talented engineers.

As an employer, Westinghouse believed fair treatment of his workers contributed to his companies’ success. In 1881, he cut his employees’ work hours to 55 hours over 5½ days. By contrast, Carnegie’s steelworkers worked seven, 12-hour shifts or 84 hours weekly.

Westinghouse and his wife were generous, anonymous donors to charities, but he believed people should rely on their own abilities to earn their way. Here is how he summarized his beliefs to an early biographer:

“I think, as a rule, a dollar given to a man does him ten dollars’ worth of harm, while a dollar honestly earned by his own efforts does him ten dollars’ worth of good; so my ambition is to give as many persons as possible an opportunity to earn money by their own effort, and this has been the reason why I have tried to build up corporations which are large employers of labor, and to pay living wages, larger even than other manufacturers pay or than the open labor market necessitates.”

Westinghouse retired in 1911. His health was failing, but he kept solving problems. Ten years before he died, he was riding in a limousine that struck a deep hole and he hit his head hard on the car’s roof. The experience prompted him to use compressed air to devise shock absorbers for cars.

Westinghouse died at age 67 in 1914. His only child, George Westinghouse III, did not live in Pittsburgh. He sold the house and 10 acres to the Engineers Society of Western Pennsylvania for $100,000. In 1918, the society deeded the property to the City of Pittsburgh for use as a park; the deed carried a stipulation that the house be demolished.

Solitude was pulled down in 1919 by collapsing it into its basement and grass was planted over it. Last October, Westinghouse Park became a designated arboretum and two magnolia trees were planted to honor George and Marguerite Westinghouse.

The indefatigable inventor left an estate valued at $50 million, an amount worth $1.3 billion today. More importantly, the value of his example as a progressive visionary, industrialist and individual is priceless.

Marylynne Pitz (mlpitz27@gmail.com) is a Pittsburgh-based arts journalist.

First Published: August 22, 2022, 10:00 a.m.

Updated: August 22, 2022, 10:58 a.m.