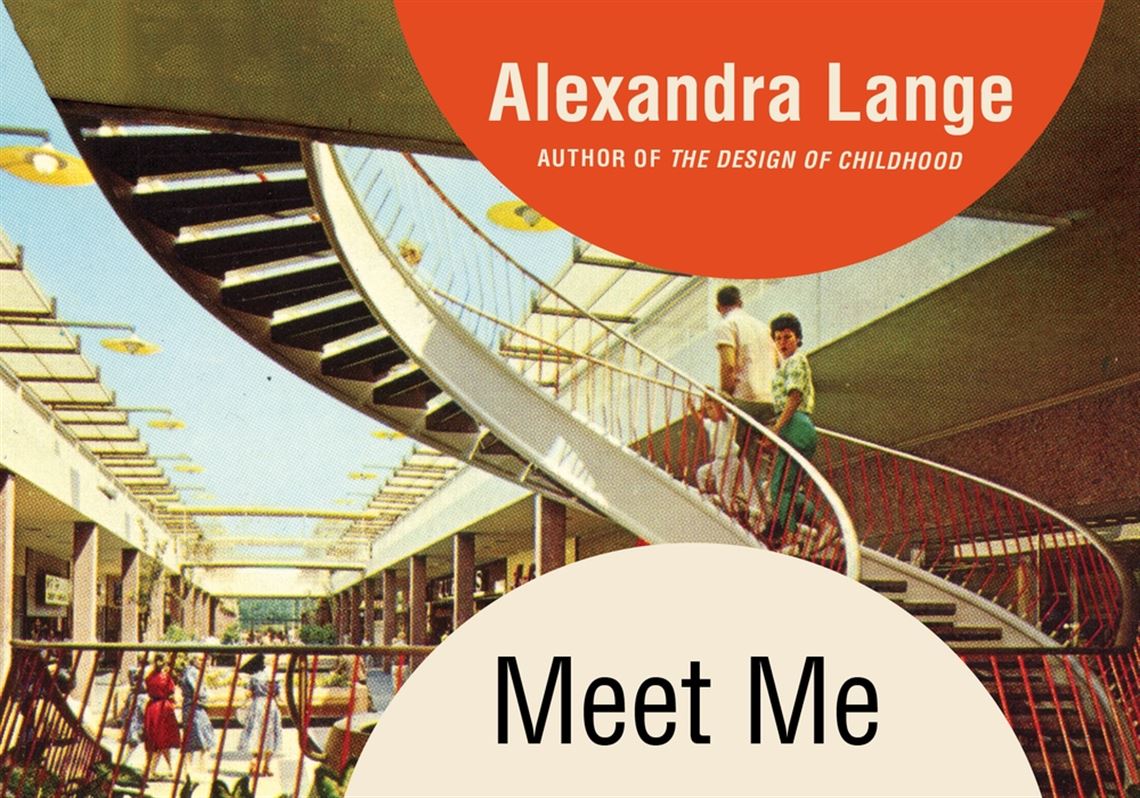

In “Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall,” design critic Alexandra Lange recalls that when she told people about her book, they reacted in one of two ways.

Bloomsbury ($28)

The first, more frequent response was to gush about personal histories with the mall: first jobs, hanging out with friends, going on dates, etc. The second was to mention dead or abandoned malls, such as those featured on “ruin porn” websites.Ms. Lange confesses to enjoying some of the online content inspired by dead malls. And she writes that she can remember the plan of her childhood mall from memory (Northgate Mall in Durham, NC).

But she’s mainly interested in charting a future for the mall in her book, and she argues that we can only do this by acknowledging how the mall has changed in the past. The first four of the book’s seven chapters trace this past, beginning with Southdale, the first fully enclosed mall in the US. Built in 1956 outside Minneapolis, Southdale created a template for future mall development because it was anchored by Dayton’s, a local department store.

Department stores have anchored malls in the US ever since and the fortunes of the two (including their recent declines) have gone hand in hand. Southdale also anticipated future mall development because it was meant to reproduce the dense, mixed-use character of the city but ended up exacerbating suburban sprawl. Southdale was designed by Victor Gruen, an Austrian émigré who arrived in New York in 1938 after fleeing the Nazis.

Gruen detested what he saw as the random, unplanned nature of the American suburbs and wanted complexes like Southdale to encourage a sense of community by offering public services and high-rise housing alongside shopping. But this ambition was repeatedly frustrated by the realities of the housing market. “No one seemed interested in the denser, mixed-use planning Gruen had imagined when, as anyone could see in a hundred other places, [single-family] houses made for an easy return on investment,” Lange writes.

This is roughly the story that Ms. Lange tells about the first 40 years of the American mall’s existence. Architects like Gruen, James Rouse, and John Jerde (who was once called Frank Gehry’s evil twin) designed shopping complexes thinking they could use commercial spaces to encourage a greater sense of community, only to have market pressures recreate the racial and class-based boundaries that existed elsewhere. And these are the architects who were trying in the first place!

Another mall history might highlight Eddie DeBartolo, who Pittsburgh readers may know as the builder of Century III mall—once the third largest mall in the US and currently a celebrity on the dead mall circuit. At one point, DeBartolo owned nearly one in 10 malls in the US and always prioritized building his empire over building community.

After this history of unrealized dreams, it’s a relief to get to the end of “Meet Me at the Fountain” and read about new ways of approaching the mall, most of which involve creating stronger connections with the community. In her final chapters, Ms. Lange offers examples of American malls welcoming local vendors, community colleges, and a wider variety local and ethnic foods. She also argues that American malls can learn from malls in other countries, for example the way they’re served by public transit.

I admit I was confused when Ms. Lange characterized these recent developments as consistent with her broader history and the mall’s fundamental “malleability,” as she does throughout the book. To me, these new approaches engage with the community in a way that differs from the top-down approaches we read about in most of “Meet Me by the Fountain.” Still, I was happy the book concluded with them, as they provide good examples of how malls can be more inclusive and democratic, and they suggest ways to enact Ms. Lange’s completely admirable belief that “architecture should serve everyone.”

Dan Kubis teaches in the English department at the University of Pittsburgh.

First Published: August 7, 2022, 10:00 a.m.