Had Benjamin Lay been only a Quaker abolitionist, he’d still be notable. During his lifetime (1682-1759), some wealthy Quakers owned or dealt in slaves, and most condoned the practice. But Lay stood out: He was a dwarf (about 4 feet tall) and a hunchback. To call him merely “an abolitionist” understates the case dramatically. Lay, who was born in England and lived his latter years near Philadelphia, in a cave, was a full-throated, all-in and relentless activist who disrupted religious gatherings with Grand Guignol acts of guerrilla political theater, and refused to use cotton or any other product of slave labor.

Beacon Press ($16)

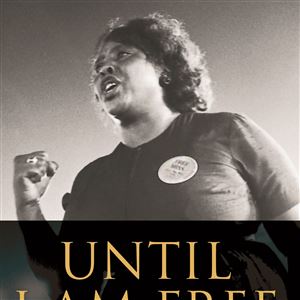

Lay earned the moniker “Prophet Against Slavery,” a title he shares with the new graphic history about him by David Lester with Marcus Rediker and Paul Buhle.

The slim 117-page book distills and narrativizes “The Fearless Benjamin Lay,” a 2017 nonfiction work by Rediker, a University of Pittsburgh history professor. With Lester’s powerful black-and-white drawings, it’s both a fascinating historical study and an implicit call to conscience.

The book’s cinematic opening sequence depicts a 1738 incident when Lay stood in the aisle of a packed Friends Meeting House in Philadelphia and plunged his sword through a book labeled “Horrors of Slavery” that spouted red liquid. The gore was just pokeberry juice, but the episode lets Lester illustrate Lay’s perspective from his verbal damning of slaveholding, to his view of Quaker leaders as fanged wolves in sheep’s clothing as well as the rancor he arouses in other Quakers.

“Prophet” sketches the roots of Lay’s deeply democratic ethos. The Quakers, the authors argue, extended the legacy of grassroots rebellion in and around Lay’s home county of Essex. Lay was also shockingly well-traveled. He spent 12 years sailing the world as a common seaman, which is how he first learned of slavery and its evils.

He and his wife, Sarah, lived briefly in slaveholding Barbados, where he saw that “sugar is made of blood.” Lay was about 50 when the couple sailed for America, where he hoped that, as advertised, true equality governed the affairs of men. He was grieved to learn that in Philadelphia, Quakers were among those who treated Black people as property.

In colonial Pennsylvania, Lay and his wife farmed and kept sheep and bees; they were also vegetarians avant le lettre. But his mission remained the same, as did Quaker resistance to it. His dramatic protests were rewarded with manhandling, flogging and repeated expulsions from congregations. (You’ll lose count of how many times he’s “cast out.”)

Lester draws in a deceptively rough-hewn style, with fiercely hatched images sometimes suggestive of woodcuts. He powerfully communicates the inflamed passions of his protagonist as well as the tenderness of more intimate scenes, like those between Benjamin and Sarah. The sight of a shoeless Lay standing in the snow at night to shame a group of Quakers outside a Friends Meeting House is among many that will stick with readers.

In his time, Lay was known beyond the Quaker community. The book depicts a visit to his cave by none other than Ben Franklin, who would publish Lay’s broadside “All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates.” While “Prophet” notes Lay’s relationship with fellow Quaker anti-slavery activist Ralph Sandiford, the narrative makes it a little hard to tell how lonely folks like Lay and Sandiford truly were in their quest. Yet there’s no doubt Lay was decades ahead of his time.

At one point, the book depicts Lay bellowing, “No justice, no peace!” — a rallying cry that still resounds at social-justice protests today. What did he change? Quakers began to prohibit slavery in their ranks shortly before his death, and the Northern states of the newly minted U.S. began phasing out the practice not too long after. Yet chattel slavery still undergirded the American economy for generations to come, and in fact became only more important in the 19th century, as cotton exports grew. A new cohort of abolitionists would pursue Lay’s dream. “Prophet Against Slavery” suggests how one era’s gadfly becomes another’s visionary hero.

Bill O’Driscoll is a Pittsburgh-based journalist and arts reporter for 90.5 WESA-FM.

First Published: November 23, 2021, 11:00 a.m.

Updated: November 23, 2021, 11:08 a.m.