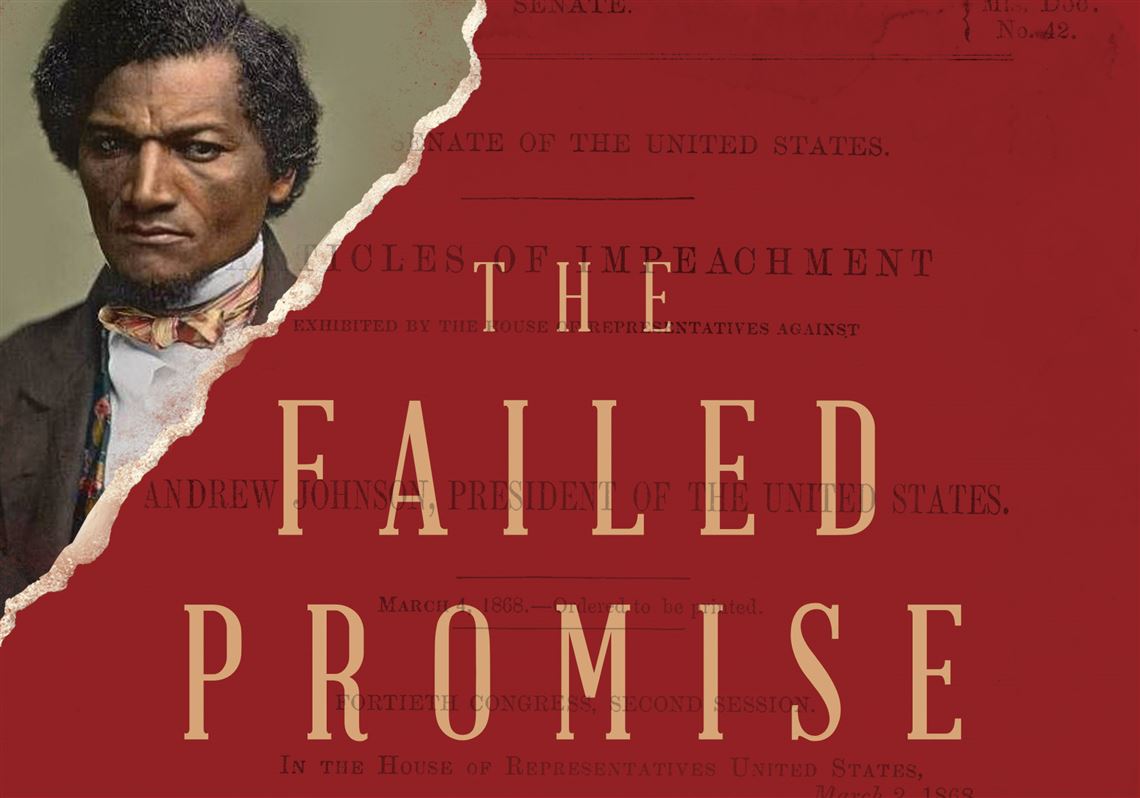

“THE FAILED PROMISE: RECONSTRUCTION, FREDERICK DOUGLASS, AND THE IMPEACHMENT OF ANDREW JOHNSON”

By Robert S. Levine

W.W. Norton & Company ($26.95)

Battles over voting rights and the meaning of citizenship. Reckless political speech that leads to bloody riots. The impeachment trial of a pugnacious president. It sounds like headlines from the last few years – in fact, these are the events captured in “The Failed Promise: Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass, and the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson,” a fresh take on the racial and political turmoil that followed the Civil War. Author Robert S. Levine uses the intersecting lives of two American leaders to probe the underlying issues of the era. In the process, he highlights struggles that continue into the present day.

Mr. Levine’s depiction of Douglass is particularly revelatory. In older histories, the famed Black orator/statesman is treated as an abolitionist hero but not as a major player in post-Civil War politics. “The Failed Promise” portrays him differently as he fights to convince white America not to abandon the cause of freedom once slavery has been ended. In this battle – waged in the press and on the lecture circuit – Douglass came to regard Abraham Lincoln as an ally. He did not feel the same about the man who inherited the presidency following Lincoln’s assassination.

Over the past century, Andrew Johnson has come to be regarded as one of America’s worst presidents. While agreeing with this assessment, Mr. Levine add nuance to his portrait, noting that he opposed slavery in his native Tennessee at the risk of his life. Towards the close of the Civil War, Johnson declared himself a “Moses of the Colored Man” who would lead the enslaved to freedom. This promise of liberation did not necessarily include the right to vote.

Mr. Levine uses Douglass’ single encounter with Johnson at the White House to contrast their opposing beliefs. He traces the conflict over reconstructing the South and shows how Johnson’s combative language and lenient treatment of ex-Confederates helped to inspire violence against Blacks in Memphis and New Orleans. Douglass bitterly condemns the president’s actions, but also finds his Republican allies’ efforts to be inadequate. In a surprising twist, Johnson offers Douglass a job in his administration – a sly co-opting move he turns down.

On a speaking tour, Douglass moves beyond condemning Johnson’s actions to point out the inherent flaws in the U.S. Constitution. He claims that the Founders gave too much power to the presidency and calls for abolishing its veto power. The office of the Vice President needed to go as well – it inspired assassination plots. Douglass said that placing Johnson in the White House was a conscious goal of Lincoln’s killers, a charge that Mr. Levine considers “a wildly paranoiac fantasy.”

Johnson’s 1868 impeachment trial is treated as a missed opportunity to hold Johnson accountable for his racist policies. Instead, Radical Republicans in Congress charged Johnson with violating the Tenure of Office Act, a law passed to prevent him from dismissing cabinet officers. Mr. Levine admits that this offered the easiest way to convict the president, though it ultimately failed by one vote. To some degree, he oversimplifies the issues in the trial and misreads the motives of its participants. At times, Mr. Levine’s book shades into advocacy and wishful thinking, though his disappointment with the Radicals’ unwillingness to confront white supremacy is understandable.

Ultimately, the reader comes away with a greater appreciation of Douglass’ courage and eloquence, as well as the sense that Johnson was less a cold-hearted villain than a representative of his time. Rather than the Moses figure he proclaimed himself to be, “Johnson was a symptom of endemic national problems that would not go away.” They haven’t yet.

Barry Alfonso, a writer and independent scholar, lives in Swissvale (alfonso.barry@ gmail.com).

First Published: September 19, 2021, 10:45 a.m.