Houghton Mifflin Harcourt ($26)

Memoirs done well are best understood as feats of literary magic. Imagine the courage required to sift through the half-forgotten details of a life lived between bouts of self-loathing, self-medicating and self-actualizing in the shadows.

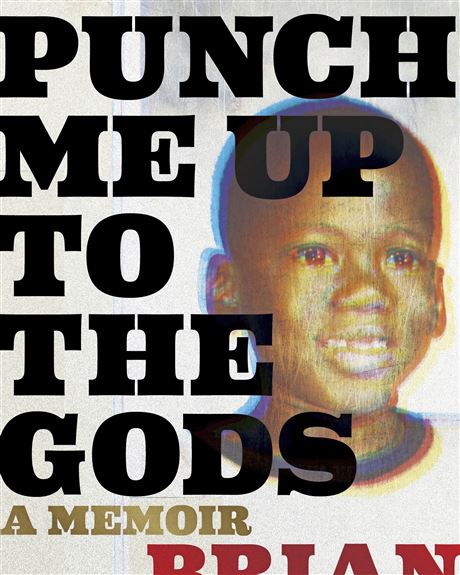

In “Punch Me Up to the Gods: A Memoir,” Brian Broome loses no time establishing his bona fides as the most fearless of memoirists who is capable of such magic.

Following Mary Karr, the genre’s finest contemporary practitioner who echoed Hemingway’s mantra, “Let me write one true sentence,” Broome gets to work putting himself on the witness stand of his own life, where the obligation to tell the truth produces harrowing testimony that makes our ears bleed at times.

Broome uses stanzas from Gwendolyn Brooks’ short poem “We Real Cool” as section headings that line up perfectly with the mood each chapter seeks to evoke.

“Punch Me Up to the Gods” is punctuated by a series of James Baldwin-inspired letters to Tuan, a toddler Broome silently communes with on a long bus ride from McKeesport to Downtown. There he will connect with a bus that will take him to the airport where he will depart to France and temporary exile in Baldwin’s shadow decades after his death.

“I board the bus behind them as I’m drawn back to my boyhood lessons of disaffectedness, nonchalance and hollow strength,” Broome writes, framing the chapters that will follow. “It was a never-ending performance that I could not keep up to save my life. And when I failed consistently, there was never any shortage of people around to punish me for it.”

Fortunately, tender observations about young Tuan’s reactions to people who get on or off the bus at each stop alternate with chapters charting Broome’s own journey from rural Ohio where being a Black, gay adolescent made him a target of his father’s wrath, to early ’90s Pittsburgh where an even deeper alienation fueled by drugs and lovelessness awaited him.

Broome is annoyed by Tuan’s father’s insistence that the boy engage in rituals of performative masculinity that made his own life a living hell decades earlier, but he is also moved by the obvious bonds of affection between father and son, an experience he never had with his own father.

“Punch Me Up to the Gods” delivers disturbing scenes of both racism in a rural Ohio and the homophobic bullying he faced at home from his unemployed father and others. Broome recounts an incident when his best friend, a popular jock he was attracted to, insisted that his effeminate friend “prove” he wasn’t gay by having sex with a girl the boys in the neighborhood had coerced into the role of testing his manhood.

In tales laced with droll humor and stoicism that would be impossible for most people to generate under the circumstances, we follow Broome’s increasingly desperate attempts to fit into whatever scene would be willing to have him. He was in denial about his sexuality and unhappy that his dark complexion made him an object of ridicule.

At one point, the racism in his town persuaded him to do his best to become “culturally white” and fit in with the white girls who befriended him. When he was invited to a school dance, he borrowed the money for the entry fee and got a lift to the remote recreation center without telling his parents who had already forbidden him to go.

It turns out that Broome was the best dancer at the dance and was the center of unaccustomed praise all evening. Still, his newfound renown didn’t translate into offers of a ride home from the bigoted parents of his white friends. Despite his very young age, he was left stranded in the cold many miles from home and forced to call his annoyed mother for a lift in the middle of the night.

When she arrived 90 minutes later, he knew what to expect.

“Her tirade continued unabated. It rose and fell and got silent and then started all over again, from shrieking to mumbling under her breath. It was only when I thought I couldn’t take it anymore that we arrived home and she put the car in park. My muscles tensed and I got ready to leap out of the car and rush to my bed to cry some more. But my mother grabbed my wrist firmly and spoke words I will never ever forget: ‘Boy, don’tchu ever trust white folks again.’”

Young Brian’s mortification is our mortification, but we’re somewhat relieved to read the words that end the chapter, even though it is clear there are many hard lessons to come:

“When Monday came, I was armed with new knowledge. It was just the white people in this small town who were the problem. I just had to go to a bigger place is all. Bless my colonized mind, I stood outside the front door of my high school, and I knew what I had to do.

“I didn’t know what internalized racism was and it would take me far too long to learn. The first period bell rang like an alarm clock, and I took my first steps forward knowing only that I had to get far away from this town.”

Whether describing the accidental burning down of his childhood home or a savage beating by his father when he is caught playing with dolls in his sister’s room, “Punch Me Up to the Gods” is full of narrative complexity and richness.

In later chapters, Broome describes getting acclimated to Pittsburgh, seeking out gay bars and hangouts and describing his quick descent into addiction. He manages to distill for the reader a chaotic social scene that most would never have encountered otherwise. He is unsentimental and unsparing in recounting his own role in what could’ve easily been a completely failed life.

Where novelists can always turn to the deniability of fiction to revisit various debaucheries with impunity, memoirists have no choice but to beg for mercy while they’re “still on the stand,” as the Leonard Cohen song goes.

But Broome’s memoir is also a harrowing tale of redemption and recovery. You would be hard-pressed to find a single cliche cluttering the flow. He is never satisfied even as he claws his way back to sobriety and the beginning of a new life of literary prestige and status.

“Punch Me Up to the Gods” can be both scalding and deeply lyrical in its takes on race, sexuality and the search for acceptance in a world that refuses to give anyone the benefit of the doubt. Through it all, Brian Broome’s voice, wise, bittersweet and always humane, never fails to remind the reader he has a long way to go on a journey he insists has barely just begun.

Tony Norman: tnorman@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1631. Twitter @Tony_NormanPG.

First Published: May 18, 2021, 10:00 a.m.