Pittsburgh was the first city in the world to use commercially generated electricity from a nuclear power plant. The year was 1957, and the plant was in Shippingport, 25 miles down the Ohio River. This was the age of “Atoms for Peace,” the idea that, 12 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear power could be used for something besides annihilation.

It was also the Cold War and the height of Pittsburgh’s so-called Renaissance, when civic leaders strained to replace Pittsburgh’s image as a provincial Smoky City with something shining and modern.

University of Minnesota Press ($30)

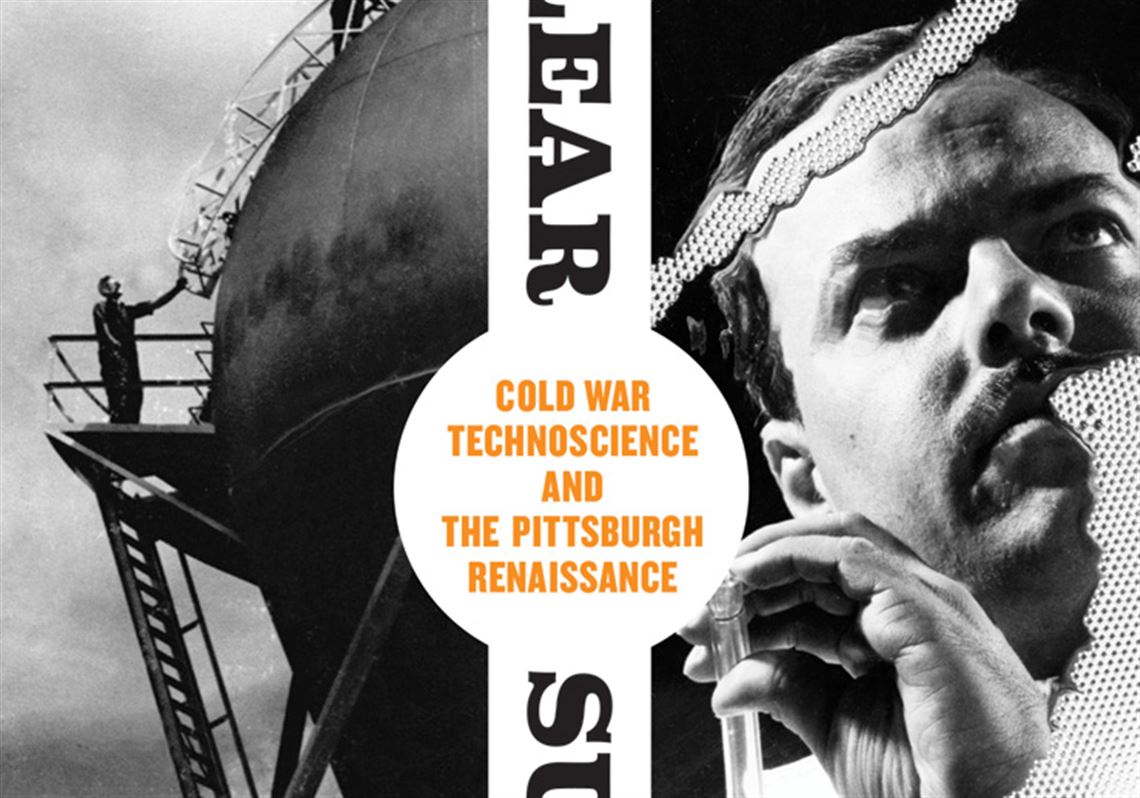

For some, then and now, this might constitute a narrative of civic pride. For Patrick Vitale, author of “Nuclear Suburbs: Cold War Technoscience and the Pittsburgh Renaissance,” it’s a chance for some critical analysis about what we call “progress” often truly means.

“Nuclear Suburbs” might suggest a campy film sendup of the 1950s, but Vitale’s tone is not amused. His goal is to show how the government and corporate officials — including Westinghouse Electric Co. — joined forces to lure nuclear research facilities to Pittsburgh, and to remake the city’s suburbs as a haven for white middle-class technologists. The strategy, Vitale argues, created prosperity for a few while Pittsburgh’s Black population and white working class were deliberately shut out.

Just as insidiously, Vitale writes, the apotheosis of scientists and engineers (and their, ahem, nuclear families) as model citizens helped enshrine technical thought as the accepted way to make public policy even though its “objectivity” routinely favored certain classes, races and genders over others. And the fact that the scientist next door was also, say, busy designing armed nuclear submarines (at the Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory in West Mifflin) simply normalized endless preparation for war.

Vitale grew up in Pittsburgh’s eastern ’burbs, in the 1980s. He’s now a geography professor at Eastern Connecticut State University, and his book, while accessible to lay readers, is more academic than not. Section headings like “The Suburban Geography of Cold War Technological Rationality” and terms like “sociospatial” are not the stuff of bestseller lists.

Vitale’s arguments are nonetheless compelling. Pittsburgh’s nuclear past was grounded in civic leaders’ fretting over the city’s image. Their desperation to attract newcomers will sound familiar to anyone who lived here in the ’90s, when the desired class was “young people.”

The affiliation of government and corporate officials known as the Allegheny Conference on Community Development pitched the renaissance partly as a bulwark against communism, Vitale shows. But for residents of neighborhoods like the Lower Hill District, it meant violent displacement by the Civic Arena and other middle-class amenities. Meanwhile, white suburbs like Bethel Park and Pleasant Hills ballooned, bolstered in part by newly minted scientists and engineers, while poorer Black city neighborhoods and river towns like Clairton dwindled.

Heaps of federal tax incentives were pumped into highways and other subsidies for suburbanites, while denser urban neighborhoods were either bulldozed for “urban renewal” or left to fend for themselves. The defense spending that seeded suburban research parks had a similar effect, a big reason Vitale sees militarism and the suburbs as malignant twins. He notes that other U.S. cities had similar experiences linking suburbanization to scientific research.

Even readers who don’t share Vitale’s political conclusions might be intrigued to learn about Pittsburgh’s place in nuclear history, which is little recalled today. The book is perhaps most interesting in its concluding chapters, when Vitale shares the results of personal interviews with 30 former industry employees, most of them scientists and engineers from the eastern suburbs. (All are white, all but one male.)

Digging into memories decades old, he plumbs their attitudes about where they lived, family life and how they viewed their work. His insight is that while they worked long hours, their conservative lifestyles away from the lab tell us even more about the society they inhabited.

The Shippingport nuclear plant was decommissioned in 1982. Westinghouse’s big corporate campus in Churchill was founded in the ’50s and active into the 2000s. It still sits right alongside the Parkway East, empty and stripped of its corporate epaulets. But much of the thinking that built it lives on.

Bill O’Driscoll is a Pittsburgh-based journalist and arts reporter for 90.5 WESA-FM.

First Published: March 30, 2021, 10:00 a.m.