In a hush-hush meeting at a Washington, D.C., law firm, consumer advocate Ralph Nader prodded Joseph “Jock’’ Yablonski to challenge W.A. “Tony’’ Boyle for the presidency of the United Mine Workers Association. As incentive, Nader offered his “all-out support.’’

The star-struck Yablonski blanched.

“If I do run, Ralph, they’ll try to kill me,’’ he said.

Yablonski ran, and lost. They killed him anyway.

Norton ($27.95)

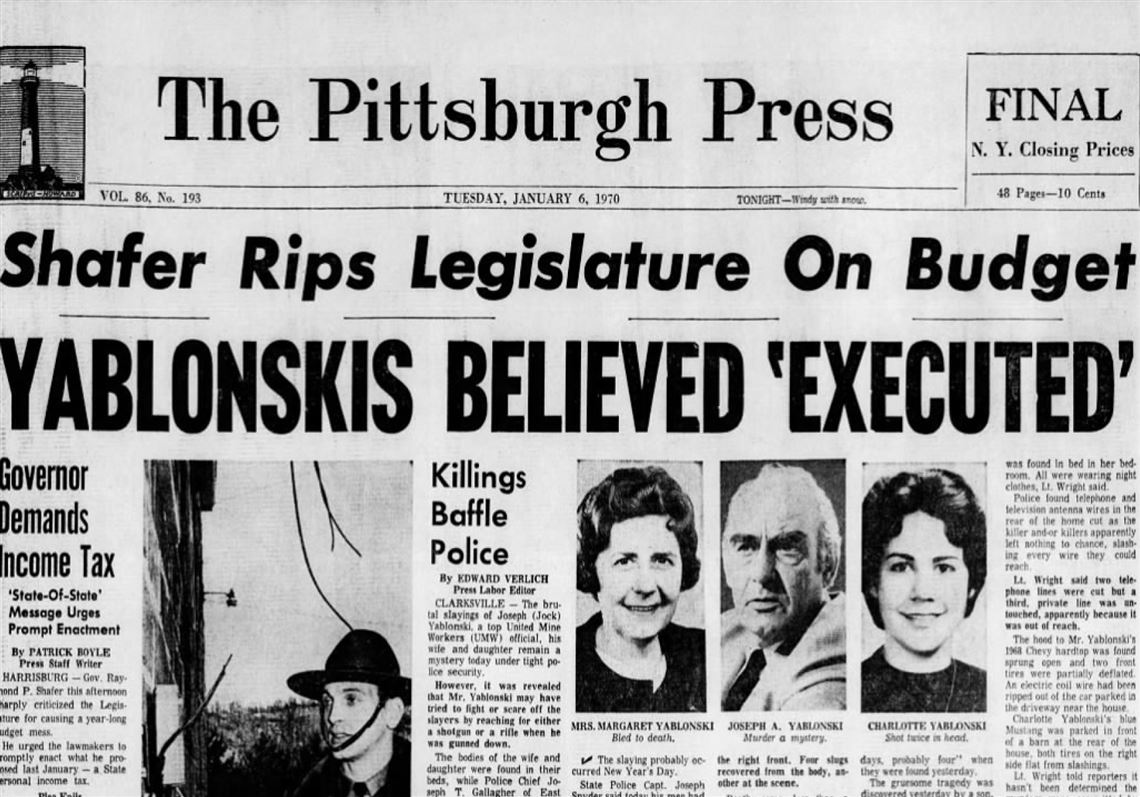

In one of the most shocking episodes in organized labor’s blood-soaked history, Yablonski, his wife and daughter were murdered in the bedrooms of their farmhouse in the rolling hills of Clarksville, Washington County, in the early hours of New Year’s Eve 1969. They were struck by nine point-blank shots fired from multiple weapons.

It took four years to bring Boyle to justice for the mob-style hit. Mark A. Bradley reconstructs the crime and the coalfield uprising it inspired in his meticulously researched book, “Blood Runs Coal: The Yablonski Murders and the Battle for the United Mine Workers of America.’’

The author is a former Justice Department lawyer, and his writing style seldom deviates from a criminal affidavit’s dry recitation of dates and facts. But when the details are this lurid and grisly, a little understatement is probably a wise choice.

The Boyle-Yablonski rivalry unfolded like a biblical parable. Both were disciples of John L. Lewis, the iron-fisted organizer who built the UMW into the most powerful union in the nation. Lewis was an autocratic ruler who didn’t shy from employing violence to keep control. Yablonski’s dreams of ascending to the throne were dashed by Lewis’ belief that his successor should be of English or Irish extraction (he was Welsh). Hence, Boyle, a descendant of Scots-Irish coal miners, became UMW president in 1963.

Yablonski, a native of Pittsburgh’s Polish Hill, reigned as president of District 5 in Western Pennsylvania when Boyle forced his resignation in 1966 over alleged financial irregularities.

Boyle was riding high in 1968 when Nader publicly accused him of looting the union’s treasury and neglecting miners’ safety. Nader revealed that Boyle had conspired with UMW treasurer John Owens to redirect $850,000 — $7 million in today’s dollars — from the union’s retirement assets to a secret bank account to fund pensions at full pay for himself, Owens and Lewis. This, at a time when bituminous miners received pensions of $115 a month.

Yablonski was 59, only a year or so from retirement, when he announced his challenge to Boyle in May 1969. His campaign was barely a month old when Boyle ordered his murder. The assignment fell to Silous Huddleston, a local union enforcer in Tennessee, who passed it on to Paul Gilly, his son-in-law in Cleveland.

Gilly and the two accomplices he hired, Claude Vealey and Aubran Wayne “Buddy’’ Martin, became became known as the “Hillbilly Hitmen’’ because of their bumbling attempts to fulfill Boyle’s contract. Their antics were like something out of a Coen Brothers movie. It took them eight tries to complete their mission. The fifth attempt was aborted when a rear tire blew out on their car barreling down Interstate 77; they took a bus back to Cleveland. Another failed when Gilly and Vealey knocked on Yablonski’s front door and presented themselves as out-of-work coal miners looking for employment. They lost their nerve and slinked off, but not before their squirrelly behavior prompted Yablonski to jot down their Ohio license plate on a desk notepad. That information led investigators to the hitmen within days of the discovery of the Yablonskis’ bodies.

Jess Costa, the Washington County district attorney, realized he was overmatched by the national and international publicity the trials would attract. He hired Philadelphia assistant district attorney Richard Sprague to handle the prosecutions. With 450 murder cases under his belt, Sprague was widely considered the best prosecutor in Pennsylvania.

Sprague more than lived up to his reputation. Pursuing justice with the righteous zeal of an Old Testament avenger, he scared Vealey into pleading guilty and flipping. He took the others to trial, and secured convictions with brutal efficiency. A jury took only 83 minutes to convict the baby-faced Martin.

Despite his prosecutorial brilliance, Sprague needed four years to work up the chain of command to get Boyle. The deposed UMWA president’s day of reckoning arrived, at last, in April 1974. The jury took only 4½ hours to convict Boyle of three counts of first-degree murder. He died in a state prison in Luzerne County on May 31, 1985, at 80.

The murders sparked a grassroots rebellion that led to the union adopting almost all of Yablonski’s 1969 reform platform. Among the changes: a new constitution, free elections and improved health and pension benefits.

Steve Halvonik is a former Post-Gazette reporter and editor who teaches journalism at Point Park University.

First Published: November 10, 2020, 12:00 p.m.