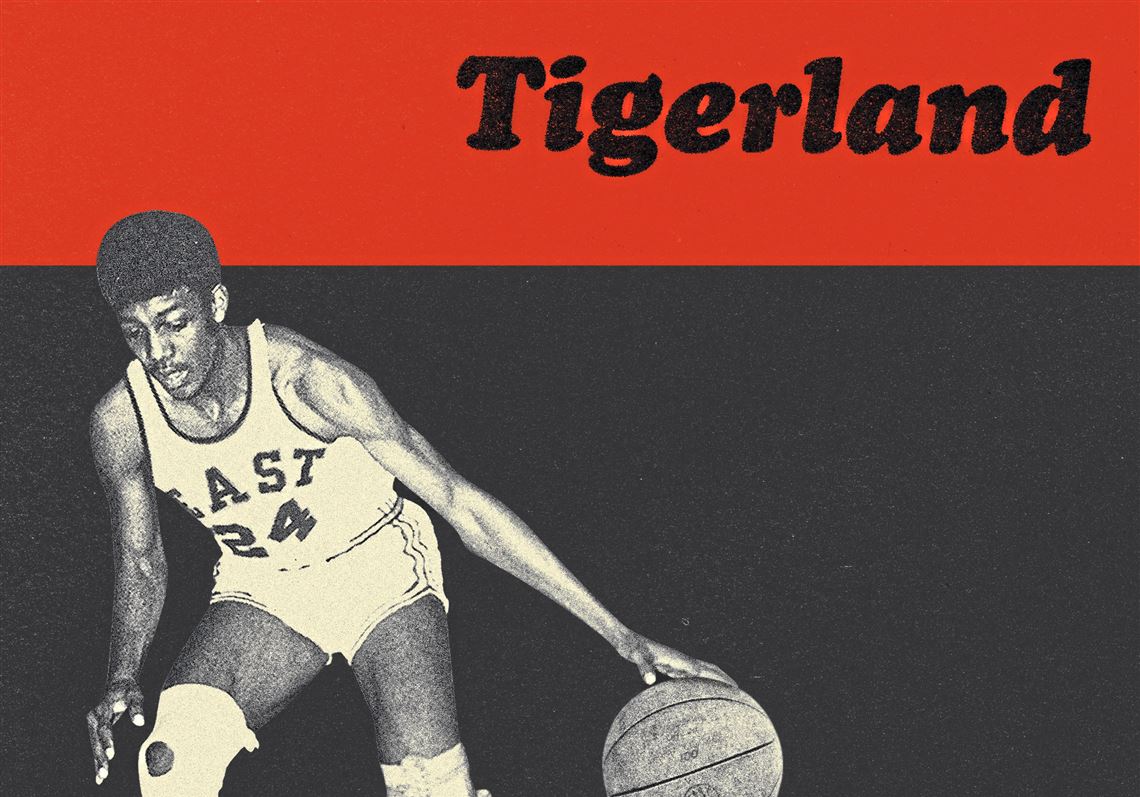

“TIGERLAND: 1968-1969: A CITY DIVIDED, A NATION TORN APART, AND A MAGICAL SEASON OF HEALING”

By Wil Haygood

Alfred A. Knopf ($27.95)

In anxious times, remember this: Tension can bring triumph. But don’t forget this caveat: Triumph can be temporary.

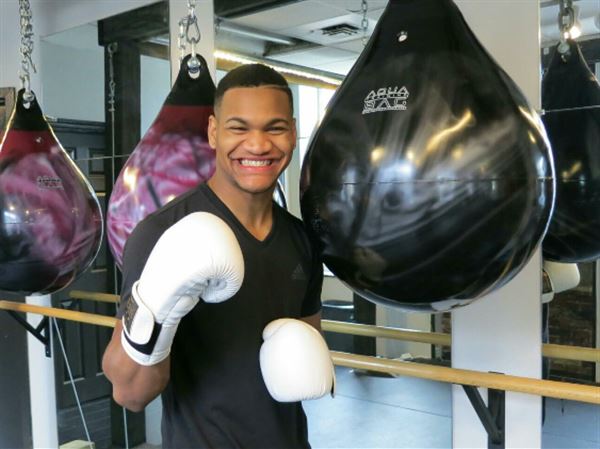

Wil Haygood, a former Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Boston Globe and Washington Post reporter and now a scholar-in-residence at Miami University of Ohio, has a history of finding an angle. He’s best known for writing the article for the Washington Post that led to the movie “The Butler,” but he’s also penned biographies of Sammy Davis Jr. and Sugar Ray Robinson.

In his eighth book, the topic is no less broad than the civil rights struggle, and the angle is a bunch of Columbus high school kids who seemed to take a tragedy personally.

In “Tigerland: 1968-1969: A City Divided, a Nation Torn Apart, and a Magical Season of Healing,” we’re taken half a century back, to a time when school segregation was technically illegal but commonplace. East High in Columbus, Ohio, was entirely black. When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April 1968, it was reasonable to think that things would never change. As some cities burned, the frustration in East High approached a boil.

So there’s cause for anxiety when a student, in the middle of an East High Tigers basketball game, starts “hollering,” and the principle, an African-American in a system stacked against his people, gets up and strides toward him. And there’s reason to wonder when the principal doesn’t silence the student but rather hands him a bullhorn. And there’s real joy when that student takes the bullhorn and belts out the school cheer:

“I went down to the river

Oh yeah

And I started to drown

Oh yeah

I started thinking about them Tigers

Oh yeah

And I came back around.”

There’s so much in that cheer. When Mr. Haygood takes us back to Emmett Till’s murder, or the many tragedies in the histories of the East High families, it’s easy to feel like we’re drowning. But Rev. King’s death seemed to focus the Tiger faithful. “The racial angst left the student body alternately with a chip on its shoulder and with a determination to cultivate its own pride,” Mr. Haygood writes.

And then we’re off on a classic sports story, as the school’s basketball and baseball players take form (especially Eddie “Rat” Ratleff, Dwight “Bo-Pete” Lamar and Garnett Davis), and the teams clamber to improbable heights. Naturally, Mr. Haygood explores the forces that shaped the young men, almost all of whom grew up in fatherless families with working mothers who struggled to feed and clothe them.

“Garnett Davis never had to look around Harley Field to see if Gardenia, his mom, had come to see him play,” Mr. Haygood writes. “’I don’t ever remember my mother coming to a game,’ he says. She was off cleaning the home of some well-to-do white family. And he certainly didn’t have to worry about his dad, Johnny Davis, showing up. He was lumbering around in the South Carolina heat, on a chain gang, because he had been convicted of murder.”

Oddly, such circumstances seem to give the Tigers an edge as they go up against teams that can actually afford new uniforms. “More often than not, most white players were not playing as if their lives depended on the sport,” Mr. Haygood writes. The blacks? “This was opportunity. The awful things that had gone wrong in their families could be righted, fixed, altered with a basketball, a football, a baseball.”

Mr. Haygood executes a series of historical fadeaway jump shots, taking us back for extended interludes with the likes of Rev. King, Jackie Robinson, federal Judge Bobby Duncan (more on him later) and other civil rights catalysts.

Sometimes the flashbacks clank off the backboard. Six pages on Richard Nixon seems a few too many, although it may be worth it for this line on his ascent to the presidency: “It was as if an ax had been taken to the great American experiment of liberalism.” Mostly, though, the interludes illustrate the forward leaps, staggering setbacks and relentlessly hard work toward equality in America.

Despite the title’s “Magical Season of Healing,” there’s no neat ending here. Like J. Anthony Lukas’ Pulitzer Prize-winning 1985 book, “Common Ground” — also focused on school segregation — there’s complexity and ambiguity throughout.

We’re glad that some of the Tigers went on to college ball, a few years in the pros, even an Olympic silver medal for Mr. Ratleff. We’re a little disappointed that true post-high-school stardom eluded them all, although each seemed to attain some degree of success.

How are we supposed to feel, though, when Judge Duncan, a Nixon appointee, issues a 1977 decision compelling the integration of the Columbus schools? When the appeals were exhausted, East’s character radically changed, becoming 55 percent white.

That’s progress, right? To stop white flight, the district modernized, adding a tech lab and “a shiny new gymnasium with many more seats.”

“Still,” Mr. Haygood writes in the epilogue, “none of that has stopped East High from, once again, becoming a 98 percent black school.”

Rich Lord: rlord@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1542. Twitter: @richelord.

First Published: September 14, 2018, 10:22 p.m.