The portability of rare books, increasing awareness of their value and the ease of selling them quickly online may have motivated someone to steal 314 rare materials and maps from the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in Oakland.

“Awareness of rare books as having a high value has increased, not the actual value of the books themselves. The book market, like the antiques market, is actually depreciating as the buyers are aging out,” said Margaret Bussiere, vice president at DeWitt Stern Group, an insurance brokerage and risk management firm in New York City.

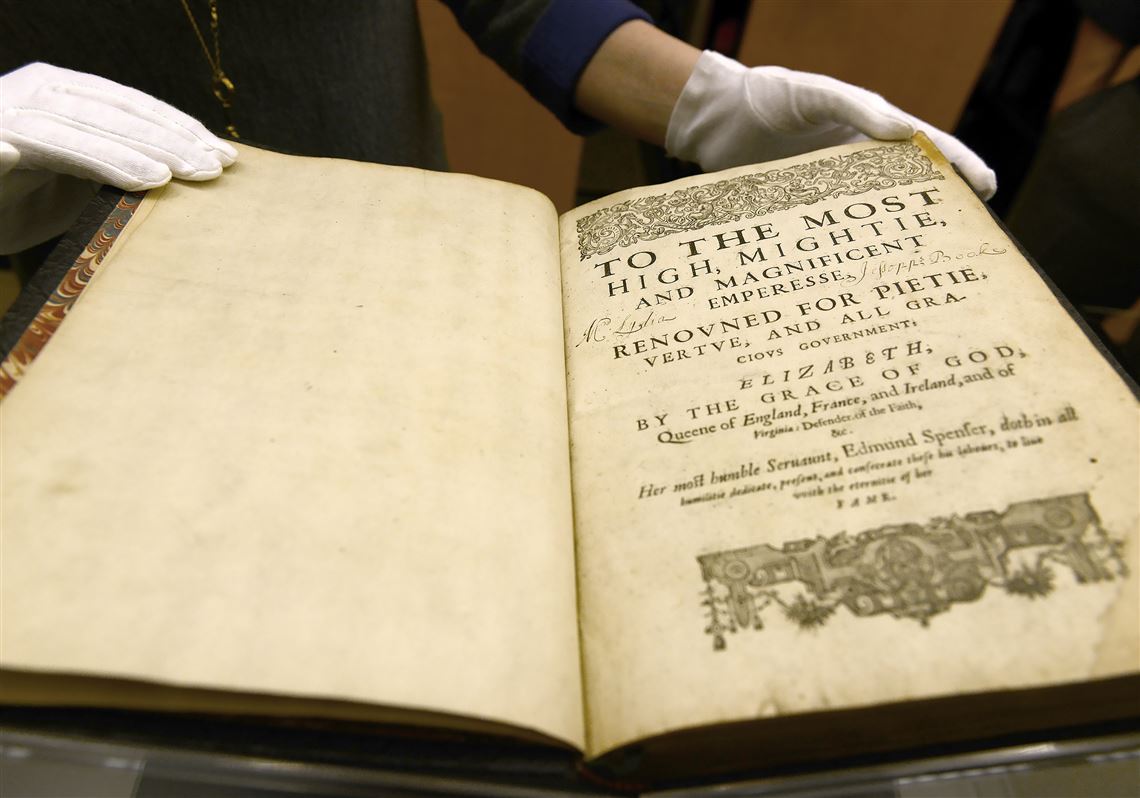

But certain rare materials that are increasing in value include medieval manuscripts and literary landmarks like Edmund Spenser’s “Faerie Queene,” one of the books stolen from the Carnegie Library in Oakland.

The theft, discovered last April during an insurance appraisal, became public this month. Three detectives from the Allegheny County District Attorney’s office have been investigating for nearly a year. At least one expert put the value of the missing items at $5 million. The library would not comment on the value.

“What I think has driven people into the book market for theft are two things: Manuscripts and the ability to carve individual pages out of them,” Mrs. Bussiere said.

“As more manuscripts are placed in libraries and museums, there are fewer left for sale. As a supply and demand type thing, then the value for very rare objects would go up. Not for the entire book market but for really rare objects. The rest is appreciating with inflation. Like jewelry, books are valuable, portable and often times indistinguishable,” Mrs. Bussiere said.

Librarians, Mrs. Bussiere added, should act accordingly.

“They should realize that when they are handing someone a rare book for study, it’s the equivalent of cash. You wouldn’t hand someone a $50,000 diamond ring and then turn your back. The key to prevention is security and visibility,” she said.

One of the most notorious thieves — E. Forbes Smiley III — stole 97 rare maps valued at more than $3 million and was sentenced to 42 months in prison. Smiley was arrested in 2005 after dropping an X-Acto blade at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Smiley used the knife to quickly remove maps from books.

“We knew exactly what he handled, “ said Edwin C. Schroeder, director of the Beinecke. Still, “We had to inventory a quarter of a million maps. That took time, just to figure out what was missing, what was not missing, doing all the footwork and paperwork.”

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s Oliver Room, tucked in the third floor stacks, holds more than 30,000 books, 50,000 archival items and 7,000 photographs. Besides Andrew Carnegie’s letters, there are books about art, Americana, architecture, music, travel, local and state history, science and technology. The room has been closed since the theft was discovered.

Earlier this month, local detectives sent a list of all missing items to the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, asking it to share the list with its members.

Charles Aston, of Squirrel Hill, recently retired from the University of Pittsburgh, where he was curator of rare books, prints and exhibits and headed Hillman Library’s special collections.

“Compared to the Rare Books & Special Collections of the Carnegie’s sister Library in Philadelphia, The Free Library, our collections in Pittsburgh have always paled in comparison of both depth & operations — which makes our loss that much more grievous, and embarrassing,” Mr. Aston wrote in an email. “Who was watching the ‘store?’!”

Librarians dislike talking about theft, Mr. Schroeder said, because they are embarrassed.

“You may or may not know what happened and you can’t explain it. That’s problematic where people want facts and you don’t know all the facts right away,” Mr. Schroeder said.

Not every missing item turns out to have been stolen.

“Is it missing? Is it just mis-shelved? Did someone take it to conservation and no one told me? Museums suffer from this problem as well,” Mr. Schroeder said. “In a rare book library, we want to know who had it when.”

At Yale, Smiley’s thievery prompted change.

“When we had the Smiley theft, we totally revamped our security operation. We didn’t have a dedicated head of security,” Mr. Schroeder said, adding that several hundred cameras were installed.

Beinecke Library staff also undertook the task of “doing a better job of describing what we had. We have to know what we actually have in order to say something is missing,” he said.

Now, Mr. Schroeder said, any bags carried by visitors or staff members are searched.

“We moved to card access. We no longer use keys. Not all staff can get to all parts of the building. We have a record of who goes in and out,” he said.

Mrs. Bussiere said clear sight lines are key so staff members have a clear view of people doing research in rare book rooms. No bookcases or stacks should block the view of visitors at reading tables.

“If you are going to have a backpack, that bag needs to be checked. Take what laptop, notebook or pens you need but the bag gets checked. Get a photo I.D. and keep a log of what material they are accessing,” she said.

“Rare book and map theft has been an ongoing issue in the industry for years,” Mrs. Bussiere added, recalling a case where a student worker at a library “would slice pages out of a book, roll them up, tuck them into his socks and go out the door. He would sell them on eBay.”

When she studied art history at Trinity College in Dublin, she said, “We weren’t allowed to access the Book of Kells. Even a facscimile was extraordinarily expensive.”

“What makes books particularly vulnerable to this kind of thing is that they are not unique. You can sell a rare book on eBay and get a lot of money for it,” she said, adding that books often lack distinguishing features, making it difficult to trace ownership.

“That’s how the stolen book trade continues to perpetuate itself. Art is harder to steal because it is unique,” Mrs. Bussiere said.

As soon as a theft occurs, libraries should notify the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America and the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers.

“You notify these organizations. It spreads very quickly,” she said, adding that librarians should search the internet for sales of stolen items.

Kierstin Ruppert, an account manager at DeWitt Stern Group, said it’s essential to update appraisals every three to five years for items that are valued at $250,000 or higher. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh did its last appraisal of its rare book collection in the early 1990s, said Suzanne Thinnes, a library spokeswoman.

“If they acquired something in the ’80s, it could have quadrupled in value. If they don’t have a fine art policy with a special valuation clause, they won’t receive full value,” Ms. Ruppert said.

Marylynne Pitz at mpitz@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1648 or on Twitter: @mpitzpg

First Published: March 22, 2018, 1:58 p.m.