Elliott Sharp is one of the most prolific and time-spanning icons in the downtown New York avant-garde music scene, along with the likes of John Zorn and Marc Ribot. Yet Sharp almost became a scientist instead, under the influence of his father in Cleveland.

"He was an industrial designer and an artist and still has his hand in it to some extent at [the age of] 87," recalls Sharp. "He designed microphones and loudspeakers in the '50s. These were always around the house, but I loved to go to his factory to listen to the huge presses punching out speaker cones. They also had an anechoic chamber, which was fun."

Sharp learned to read thanks to an interest in science fiction. "It was the Space Age, so I wanted to study to be an scientist," but music also beckoned. "I was studying classical music on piano, and then clarinet after the piano kind of drove me crazy. I was into bands like The Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones, and Jeff Beck's guitar playing. I got my first guitar in 1968 and took it with me to Pittsburgh."

No Pittsburgh article about Sharp would be complete without mentioning his short but formative sojourn at Carnegie Mellon during his 17th year.

- Where: Andy Warhol Museum, North Side, 412-394-3353

- When: 8 p.m. Saturday

- Tickets: $10-$15 general, $5-$8 students, www.music.pitt.edu

- Also: Sharp gives a talk at the University of Pittsburgh Music Dept, Room 123, 1 p.m. Saturday. Free to the public.

"I was an assistant in lab -- we had lectures and chose projects. I also got myself a slot at WRCT-FM deejaying from midnight to 4 a.m., and I was free to play the weirdest stuff I found in their library -- composers like Stockhausen, Xenakis and Partch, and all kinds of psych records like the 13th Floor Elevators. But the station manager fired me after a few weeks -- he decided the station should follow a Top 40 format."

Involved in anti-war activities and an underground newspaper in his high school, Sharp moved further away from his scientific dream after he saw how it was funded. "So much [money] came from the Defense Department. And I didn't like the hierarchical structure with people always groveling for grants. But music was exciting -- I could do experiments on a sonic level, building fuzzboxes and filters and using tape decks. When I went to college at Cornell, I was in the anthropology department, but there were a lot of musicians playing in rock bands. I began to listen more to free jazz and Miles Davis, and, of course, Captain Beefheart and Jimi Hendrix."

In the master's program at Buffalo, Sharp found his calling as a composer, studying with major 20th-century new music figures Lejaren Hiller and Morton Feldman. "Hiller was important -- he approached composition by working within a set of gestures or syntax, and I liked that way of operating. Feldman lorded over the department. I learned a considerable amount listening to him pontificate at his weekly forums, but he didn't like my music. He said, 'You put too much sociology in it -- music should be listened to sitting in red plush seats, and yours is for sitting on the floor!' "

While Sharp eagerly joined the downtown New York improvised music scene ("improvising is very much a social function -- it's like having a good conversation over a dinner table") that had begun to percolate alongside punk and No Wave at the beginning of the '80s, most people probably first heard of him on a series of amazingly dense and complex albums issued by the California indie label SST, also responsible for launching the careers of Sonic Youth, Black Flag and the Meat Puppets.

Yet by 1984, Sharp had also written his first string quartet, "Tessellation Row," for the Soldier String Quartet. A quarter-century later, Sharp still maintains a strong connection with ex-Soldier violist Ron Lawrence, who's now in the Sirius String Quartet -- which will play two of Sharp's pieces Saturday at The Warhol, namely "Dispersion of Seeds" and the U.S. premiere of "Volpak," featuring Sharp on guitar, along with works by Henry Cow guitarist Fred Frith and German composer Gregor Huebner.

"I always liked the string quartet -- it's like a rock power trio. I have a large body of them -- I'm working on my 18th for a young New York ensemble, but I've been played by Arditti and Kronos. The orchestra is like a giant additive synthesizer with an ancient operating system," he expounds scientifically. "But all it knows how to do is read pieces of paper with black dots in the proper places. So if you have your own orchestra, you can be experimental as much as you want. That's what I've done with [ensemble] Orchestra Carbon, mostly algorithmic pieces. [My piece] "Syndikit" is like a primordial soup -- there's 144 composed segments, 12 players each get 12 of them and a set of rules where they can make loops, combine, imitate other people, transform, or do short improvised parts as a way of introducing mutations."

Indeed, much of Sharp's work has taken quite a mathematical route, dealing with topics such as fractal geometry, chaos theory, genetics and Fibonacci numbers. So when Sharp wants to bust loose from his lab coat, he steps out to tour Europe with a blues band called Terraplane, which recently has included Howlin Wolf's longtime guitarist Hubert Sumlin. "Without him, there'd be no Clapton or Page -- they all copped from Hubert," Sharp says. "We're not a fixed Chicago-style band. Terraplane stretches it a bit with one foot in the past and one in the future, [because] that's how you put your [behind] in the present."

In between, Sharp has found time to write interstitial music for MTV (one of his contributions wound up as the theme for the "Carmen Electra Show"); record albums with the likes of Japanese noise champion Merzbow, Wilco guitarist Nels Cline, and jazz drummer Bobby Previte; and work with Middle Eastern musicians such as oud player Elias Khoury, Master Musicians of Jajouka leader Bachir Attar, and legendary qawwali singer, the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. "I don't share his spiritual beliefs, but to listen to [Nusrat] sing is like hearing Coltrane play. We were both playing a concert in Montreal, and the McGill radio station asked if we'd collaborate. My approach was just to fit in with what he did -- drones and some ornamentation."

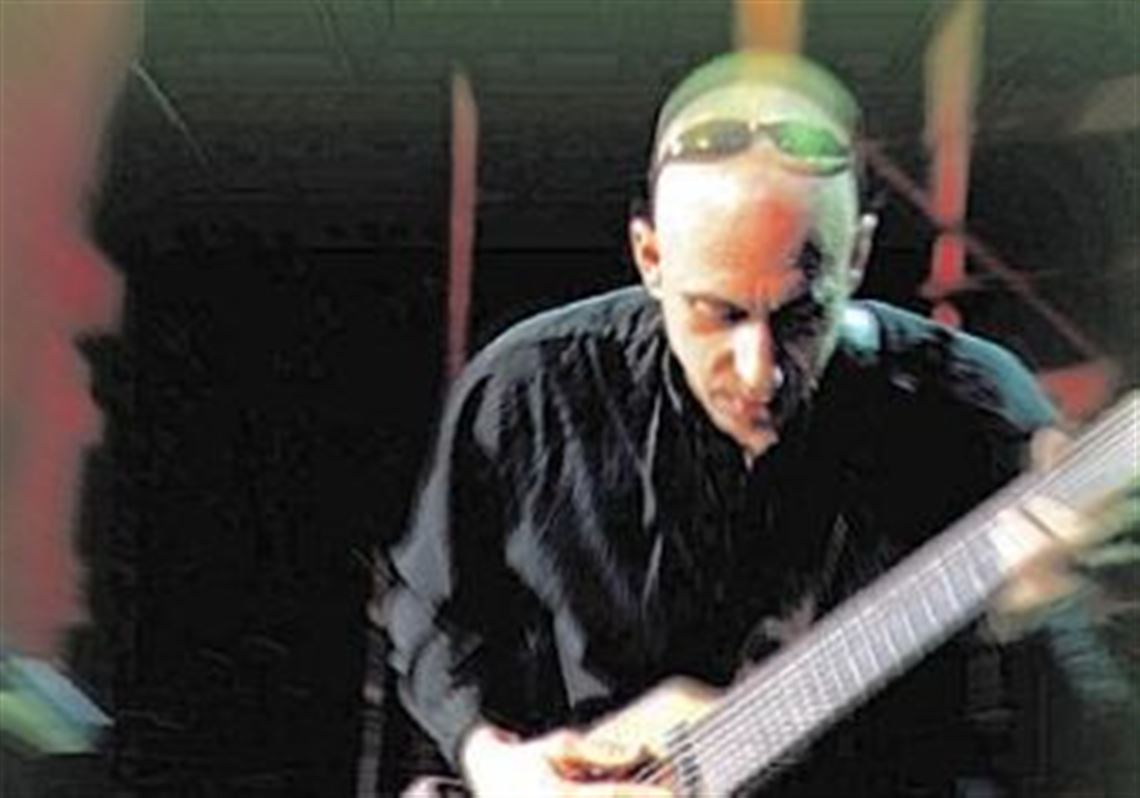

However, Sharp is probably best known for his distinctive guitar sound, which he'll showcase on Saturday in a solo work called "Momentum Anomaly." "I have a certain vocabulary of sound I've developed from playing. Sometimes I try to set up a situation where I have no idea what the outcome will be, or I'll set up a tuning from some mathematical system, new electronics or hardware I haven't used before, so there's an element of play. I've created a style based on experiments that I've done -- the two-hand tapping thing I did for many years before [Eddie] Van Halen did it. It's a basic part of my playing, as is working with harmonics in a very different way than what, say, [British guitar improvisor] Derek Bailey was doing."

Nowadays, Sharp has to make his creative time more efficient since he's had twins, now 3 years old ("for me, they're the most absolutely joyous thing") with his wife, Janene Higgins. "Now that so much more of my work is composing, it takes a lot of time, even using a computer. So I try to do it while I'm doing other things. I might wake up in the middle of the night and work on music for an hour, then try to remember what I've done when I get back to the studio."

Despite his large body of work, Sharp still isn't regarded as a "composer" by the New Music establishment in America, so he continues to focus on work overseas, and doesn't even appear that much in Manhattan, where opportunities have dried up. "There are some places, but no real scene anymore. There's a bit of a Brooklyn jazz scene, but I'm not part of that. Maybe if real estate prices start dropping, there'll be a chance for new music venues to pop up again. The health of an art scene is tied to the price of buildings, because if you have people worried about making their rent, they're not going to have time for being creative. New York has been very much about [the cramped quarters of] four people sharing an apartment."

The Internet, with its effect of decentralization, has also "taken the blood" out of some vibrant music scenes, Sharp contends. Yet for him, the devaluation of recorded music (via downloading and file-sharing) has produced one excellent result. "Live concerts are more vital now than they've been for a while. When I perform in Europe, people are very excited about being in a room with musicians playing live, making mistakes and sweating. It's a visceral experience, and it should be."

First Published: January 8, 2009, 10:00 a.m.